_______________________________The Class 12 History Chapter 11, “Mahatma Gandhi and the Nationalist Movement” is one of the most important chapters for:

- CBSE Class 12 Boards

- CUET (UG)

- UPSC/State PCS basics

- Competitive exams needing modern Indian history

INTRODUCTION TO THE CHAPTER

The chapter studies:

- Gandhi’s emergence as a mass leader

- How he transformed the Indian National Movement

- Philosophical foundations of his politics

- His major movements (NCM, CDM, QIM)

- His relationship with peasants, workers, women, Dalits, tribals

- His negotiations with the British

- Conflicts between Gandhian and non-Gandhian nationalism

- Visual sources (cartoons, popular imagery, photos)

WHY GANDHI IS CENTRAL TO INDIAN NATIONALISM

Before Gandhi, the national movement was:

- Elite-driven

- Led by lawyers, professionals, educated Indians

- Dominated by Moderates and Early Nationalists

- Methods included petitions, resolutions, polite constitutionalism

- Limited participation

- Very little involvement of peasants, tribals, women, workers

- Movements confined to urban centers

- Fragmented leadership

- Moderates vs Extremists (Tilak, Bipin Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai)

- Revolutionary terrorism rising in Bengal, Punjab, and Maharashtra

- No unifying method, ideology, or national message

- Limited moral or symbolic power

- Movements challenged policies, but not the moral legitimacy of British rule

Gandhi completely changed this landscape.

Gandhi’s transformative impact:

- Nationalism became a moral, social, and mass movement, not just political negotiation.

- Ordinary Indians—from peasants to tribals, women to students—became political actors.

- The struggle became non-violent, disciplined, and ethically grounded.

- Movements were linked with swadeshi, khadi, self-reliance, and ethical living.

- Gandhi built a nationwide organization through ashrams and volunteers.

- His image became the symbol of Indian resistance globally.

Thus, to understand Indian nationalism, one must understand Gandhi.

GANDHI’S EARLY LIFE AND FORMATIVE INFLUENCES

To understand Gandhi’s later political philosophy, students and teachers must study:

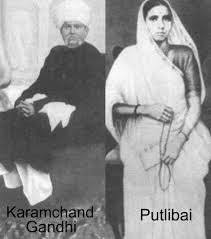

1. Family and Religious Background

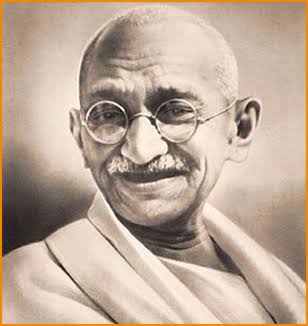

- Born on 2 October 1869, Porbandar, Gujarat

- Grew up in a Vaishnava household

- Strong influence of his mother Putlibai—piety, fasting, compassion

- Influence of Jain philosophy through Gujarat’s religious environment

- Ahimsa (non-violence)

- Aparigraha (non-possession)

- Anekantavada (many-sided truth)

These values shaped Gandhi’s later political methods (fasts, non-violence, tolerance).

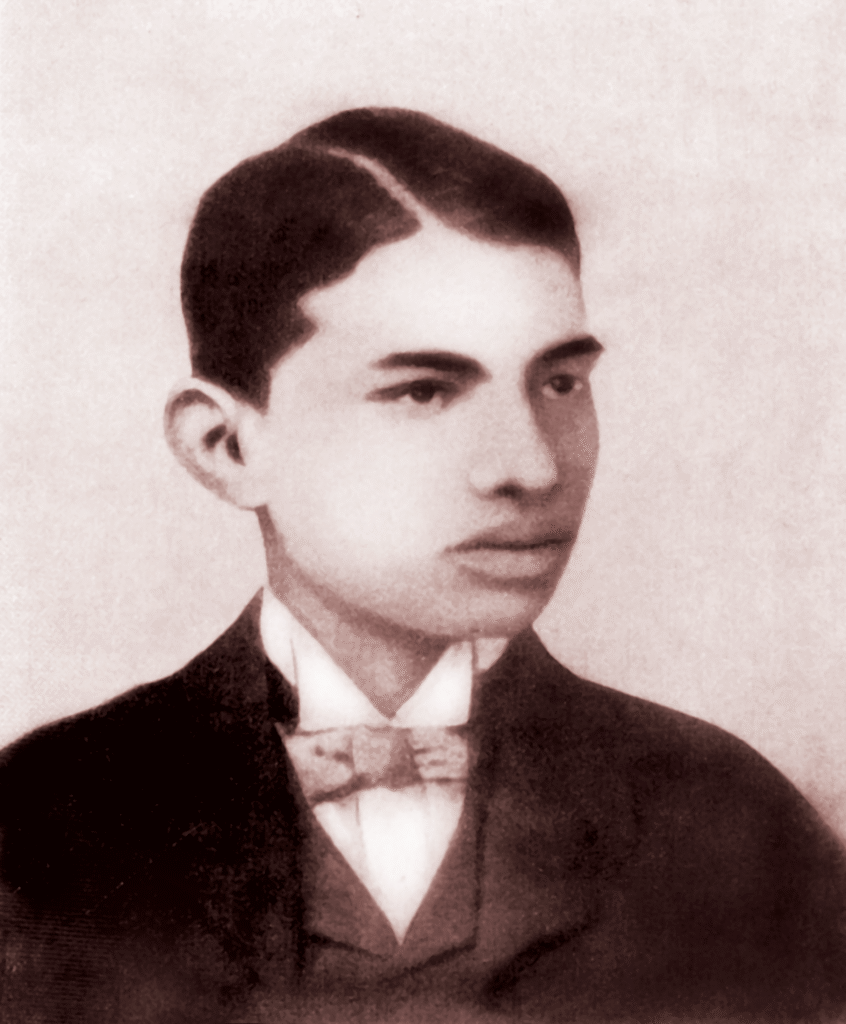

2. Education in London (1888–1891)

Here Gandhi was exposed to:

- Western political thought (Ruskin, Thoreau, Tolstoy)

- Vegetarianism and moral discipline

- Liberal, constitutional ideas

- Ethical and social reform movements

He learned:

- Public speaking

- Debating

- Peace activism

- How to combine morality with politics

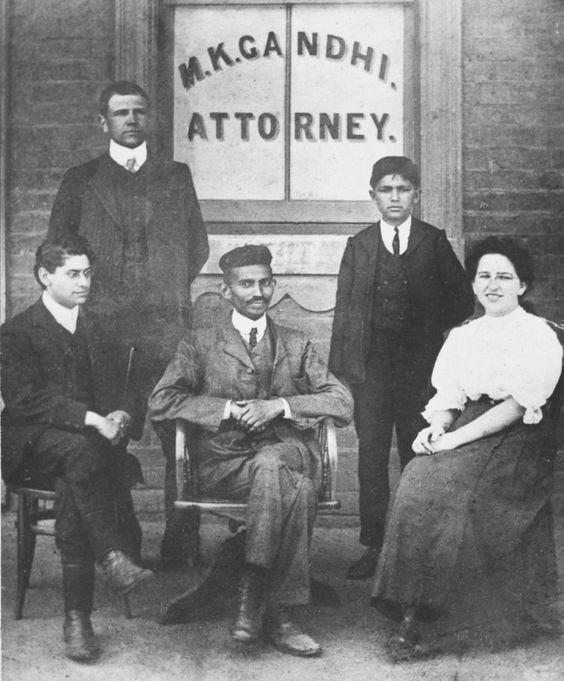

3. South Africa: The Crucial Turning Point (1893–1914)

Gandhi’s two decades in South Africa shaped his entire ideology.

Major Lessons Gandhi Learned

- How racial discrimination operates

- Thrown out of a train at Pietermaritzburg

- Humiliated repeatedly

- Understood that injustice is institutional, not personal

- Community organization

- Formed the Natal Indian Congress (1894)

- Mobilized Indian workers, traders, professionals

- Satyagraha experimented for the first time (1906)

- Truth + Non-violence + Civil Disobedience

- Mass discipline, willingness to suffer

- Importance of simple living

- Established Phoenix Settlement, Tolstoy Farm

- Live close to nature, remove inequalities

- Moral purity = political strength

- Negotiation and moral pressure

- Realized British respond to moral criticism

- Law-breaking must be non-violent and transparent

Thus, South Africa was Gandhi’s political laboratory.

India would become the field of application.

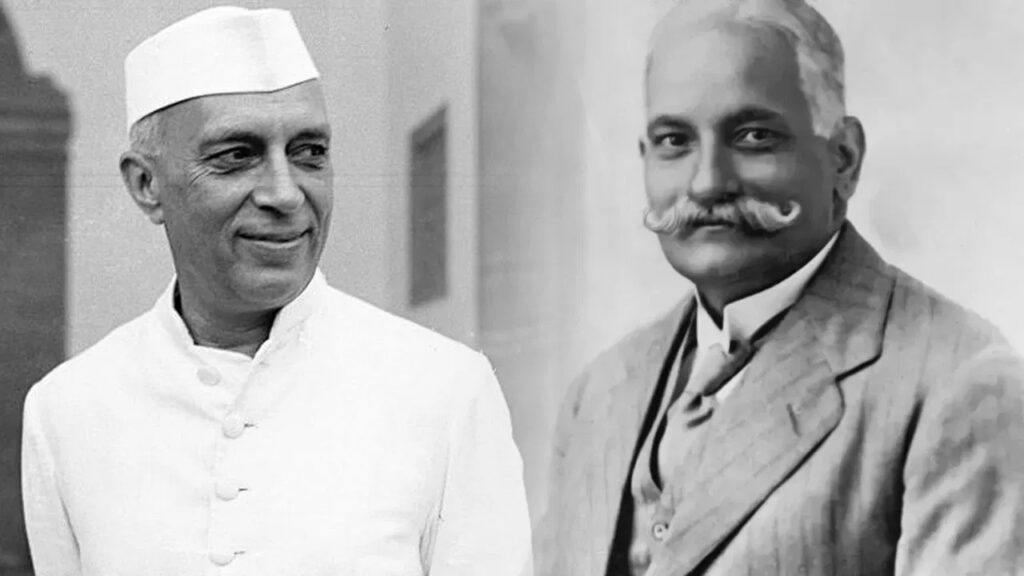

GANDHI RETURNS TO INDIA (1915)

He returned as a somewhat known figure, but not yet a national leader.

Entry through Moderates

- Welcomed by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, mentor and respected Moderate leader

- Asked Gandhi to travel across India before entering politics

- Gandhi obeyed → travelled to villages, towns, cities

- Understood poverty, oppression, caste, agricultural misery, and British structure

This period was Gandhi’s political apprenticeship in India.

His decision:

He would not join politics through speeches, but through local action and moral leadership.

GANDHI’S EARLY SATYAGRAHA EXPERIMENTS IN INDIA (1917–1918)

These three movements are crucial because:

- They gave Gandhi national credibility

- They revealed his method: investigation → negotiation → non-violence → moral victory

- They showed his concern for peasants and workers

- They were test cases of Satyagraha in Indian conditions

NCERT mentions these briefly, but for CUET and competitive exams, they must be studied deeply.

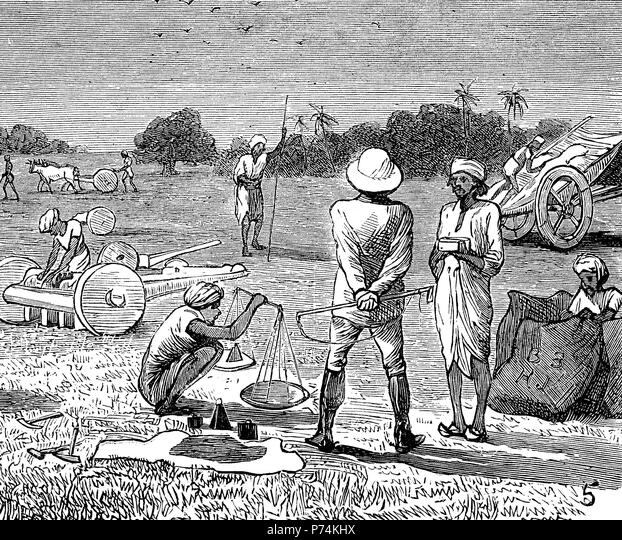

1. CHAMPARAN SATYAGRAHA (1917) – Gandhi’s First Satyagraha in India

Background

- Champaran (Bihar) was a major indigo-growing region

- European planters forced peasants into the tinkathia system

- 3/20th of land must be used for indigo

- Forced cultivation

- Rent, illegal cesses, harassment

- After German synthetic dyes arrived, planters shifted losses to peasants

- Peasants had no legal recourse

Local activist Raj Kumar Shukla persuaded Gandhi to visit.

Why Champaran was significant

- Gandhi broke British order: he refused to leave Champaran

- Began fact-finding: collected statements of thousands of peasants

- Turned a local grievance into a moral-national issue

- Negotiated directly with planters and government

- Appointed to a committee of inquiry

- Ultimately → Tinkathia abolished

Gandhi’s strategy here reveals:

- He preferred truth-finding over instant protest

- Satyagraha is moral persuasion, not political coercion

- Mass movements must begin with real local suffering

- Peasants must become conscious participants, not passive victims

2. AHMEDABAD MILL STRIKE (1918)

This movement brought Gandhi into contact with industrial labourers.

Background

- Textile mill owners of Ahmedabad and workers were in dispute over plague bonus

- Owners wanted to withdraw the bonus

- Workers demanded a 35% wage increase

Gandhi’s Role

- Gandhi mediated between mill owners (including Ambalal Sarabhai) and workers

- When owners refused, Gandhi asked workers to strike peacefully

- When workers showed signs of fatigue, Gandhi undertook a fast-unto-death,

believing the leader must share the suffering of his followers

Outcome

- Mill owners agreed to a 35% wage increase

- Gandhi’s moral authority rose

- Revealed Gandhi’s innovative use of self-suffering as a tool of negotiation

3. KHEDA SATYAGRAHA (1918)

This was Gandhi’s first large-scale peasant campaign in Gujarat.

Background

- Kheda district suffered crop failure

- According to revenue rules, taxes should be remitted

- Government refused to give relief

- Farmers faced debt, drought, and pressure from officials

Local leaders:

- Vallabhbhai Patel

- Indulal Yagnik

Gandhi’s Strategy

- Advising peasants to withhold revenue

- Complete non-violence and unity required

- This was not a no-tax movement → it was legal non-payment

Outcome

- Government suspended revenue collection

- Returned seized lands

- Recognized the demands of peasants

Why these three satyagrahas matter for exams

They show Gandhi’s core principles:

1. Empathy and investigation before agitation

He learned the truth by witnessing suffering.

2. Mass moral awakening

Ordinary people became part of national politics.

3. Ahimsa and Satyagraha as practical tools

Not abstract philosophy → political action.

4. Making the British morally accountable

Gandhi’s movements made colonial rule appear unjust before the world.

5. Cooperation with local leaders

He elevated Vallabhbhai Patel, Rajendra Prasad, and others.

These movements made Gandhi the natural leader of India by 1919.

THE POLITICAL SCENARIO BEFORE THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT (1919)

Before Gandhi launched his first nationwide agitation, India was in turmoil:

1. World War I impact

- Economic crisis

- High taxes

- Food shortage

- Rising prices

- Recruitment of soldiers from villages → suffering

2. British wartime repression

- Sedition laws

- Censorship

- Arrests

3. Muslim discontent over the fate of the Ottoman Caliph

- This will lead to the Khilafat Movement

4. Influenza epidemic (1918–19)

- Killed millions

- Government response was weak

5. Rising expectations

- Indians expected political rights after supporting Britain in WWI

- British instead passed the Rowlatt Act

This sets the stage for Gandhi’s first nationwide movement.

GANDHI’S RISE TO NATIONAL LEADERSHIP (1919–1922)

Rowlatt Act, Jallianwala Bagh, Khilafat, and the Non-Cooperation Movement

THE ROWLATT ACT (1919) – THE FIRST NATIONWIDE SATYAGRAHA

After Gandhi’s successful local satyagrahas (1917–18), India faced a political shock that changed the direction of nationalism.

1. Why the Act Was Introduced

During World War I, the British government had implemented wartime emergency laws to suppress political opposition. After the war ended, Indians expected that these extraordinary laws would be withdrawn.

Instead, in 1919, the British government permanently extended these repressive powers through the Rowlatt Act, recommended by Justice Sidney Rowlatt.

2. Features of the Act

- Political activists could be arrested without warrant.

- Trials would be held without juries.

- No right to appeal in higher courts.

- Police surveillance could be extended indefinitely.

- Effectively suspended basic civil liberties.

It was called the “Black Act” by Indian nationalists.

3. Gandhi’s Response – Nationwide Hartal

Gandhi was shocked. The Act convinced him that:

British rule had become morally illegitimate.

He declared a nationwide hartal (strike) on 6 April 1919.

What made this special?

- First all-India mass movement under Gandhi.

- Peasants, workers, artisans, urban poor – all participated.

- Complete non-violent civil disobedience was planned.

- Hartal = closing shops, fasting, prayer, peaceful marches.

Gandhi called it a “Satyagraha of the spirit”.

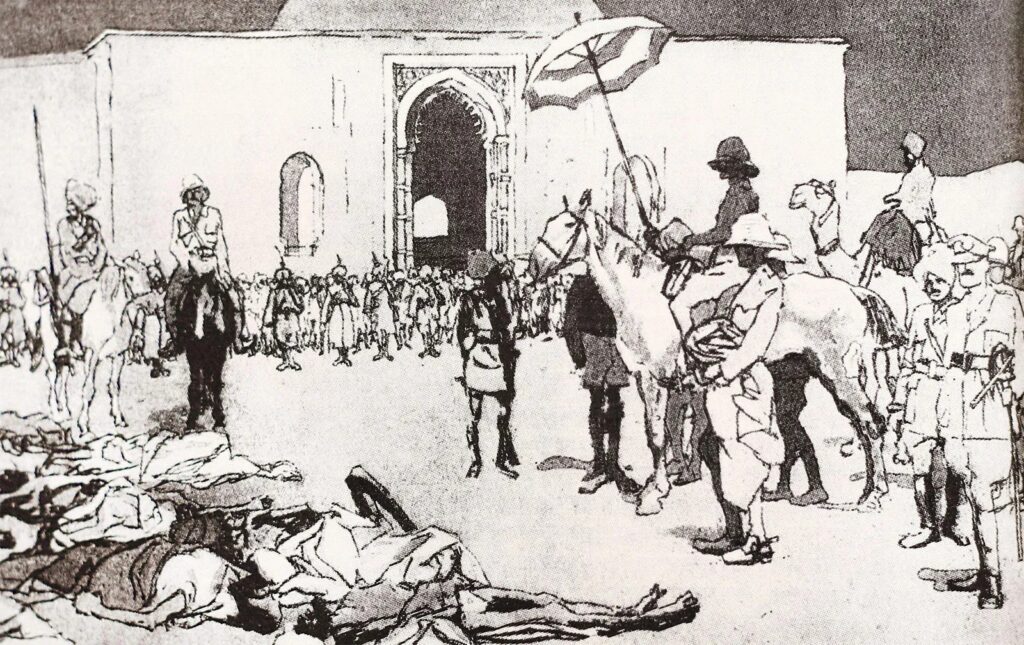

THE JALLIANWALA BAGH MASSACRE (13 APRIL 1919)

1. Context

Punjab was one of the most politically active provinces.

Two nationalist leaders—

- Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew,

- Dr. Satyapal

—were arrested in Amritsar on 10 April.

Protests erupted. The army was called.

2. The Massacre

On 13 April, Vaisakhi day:

- A peaceful crowd gathered in Jallianwala Bagh, a walled ground with narrow exits.

- General Reginald Dyer marched in with troops.

- Without warning, he ordered open fire.

- Men, women, children were trapped.

- Around 1,000 people killed (British figure claims 379; Indian estimates are much higher).

Dyer later confessed:

“I wanted to teach a moral lesson… to produce a wide impression.”

3. Impact on India

- Nationwide grief and anger.

- Rabindranath Tagore returned his knighthood.

- Gandhi called it the “first great blow to British moral authority.”

- Public faith in constitutional politics was destroyed.

This tragedy transformed Indian nationalism emotionally and morally.

THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT

After Jallianwala Bagh, another major issue unfolded: the future of the Ottoman Caliph, the spiritual head of the global Muslim community.

1. Background

- Turkey had lost World War I.

- British planned to dismember its territories.

- Indian Muslims feared disrespect to the Caliph (Khalifa).

- Muslim leaders formed the Khilafat Committee (1919).

Key leaders:

- Maulana Muhammad Ali

- Maulana Shaukat Ali

- Maulana Abul Kalam Azad

- Hakim Ajmal Khan

- Hasrat Mohani

2. Gandhi Joins the Khilafat Cause

Gandhi saw two advantages:

(a) Hindu–Muslim unity

A joint movement would prevent communal division.

(b) A united national struggle

Khilafat grievances + Indian political grievances = single mass movement.

Thus, Gandhi became the most respected leader among Indian Muslims at this time.

THE NON-COOPERATION MOVEMENT (1920–1922)

This was the first full-fledged, nation-level satyagraha led by Gandhi.

1. Reasons for Launching the Movement

- Jallianwala Bagh massacre

- Rowlatt Act

- Khilafat injustice

- Repressive martial law in Punjab

- Rising economic distress

Gandhi declared:

“Cooperation in evil is a sin. Therefore non-cooperation is a duty.”

2. The Programme of Non-Cooperation

The movement aimed at peaceful withdrawal of support from British institutions.

Stage 1: Renunciation of titles and honors

- Students to leave government schools and colleges.

- Lawyers to boycott courts.

- Citizens to refuse government services.

- People to resign from government posts.

- Boycott of elections to councils under the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms.

Stage 2: Economic Boycott

- Boycott foreign cloth.

- Burn imported items.

- Promote swadeshi and khadi.

- Rebuild Indian village industry.

Stage 3: Widespread Satyagraha

- Establish national schools and panchayats.

- Replace British law courts with informal arbitration courts (panchayats).

- Promote social reform—swachhata, removal of untouchability, prohibition.

Gandhi believed that if Indians withdrew cooperation, the Raj would collapse like a house of cards.

3. Why the Movement Became a Mass Upsurge

(a) Peasants

- High rents, unpaid begar (forced labour), and brutal landlords.

- Found hope in Gandhi and nationalism.

- Uttar Pradesh (Awadh), Andhra, Punjab, Bengal saw mass mobilization.

(b) Tribal communities

- Anti-forest laws.

- Restrictions on grazing and shifting cultivation.

- Tribal revolt in the Rampa forests (Andhra) took inspiration from Gandhi.

(c) Students and teachers

- Thousands left government schools.

- National educational institutions flowered.

(d) Lawyers

- C.R. Das, Motilal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, T. Prakasam left law practice.

(e) Merchants

- Saw an opportunity to replace foreign cloth with Indian products.

(f) Women

- Widespread participation in picketing, spinning, protests.

- But Gandhi still did not support their participation in armed struggle—only non-violent activism.

4. The Movement Becomes Truly National

- Bengal → Massive boycott of foreign cloth.

- Assam → Using khadi became a cultural symbol.

- Punjab → Trade unions and peasants joined.

- South India → Devadasis, students, coffee workers participated.

- UP/Awadh → Against taluqdars and oppressive landlords.

The British were shocked:

Gandhi had turned the Congress from an elite political body into a mass movement representing India.

SWARAJ DEBATE INSIDE THE CONGRESS

Not everyone agreed with Gandhi’s strategy.

1. Moderates

- Believed constitutional methods should continue.

- Thought Non-Cooperation would destroy progress of earlier decades.

2. Some Extremists

- Supported Gandhi but felt non-violence limited mass anger.

3. Congress Leaders Fearful of Anarchy

- Lala Lajpat Rai, C.R. Das, Motilal Nehru worried about mass upsurge turning violent.

Despite debates, Congress adopted Non-Cooperation unanimously at the Nagpur Session (1920).

This united front made the movement powerful.

HEIGHT OF THE NON-COOPERATION MOVEMENT (1921)

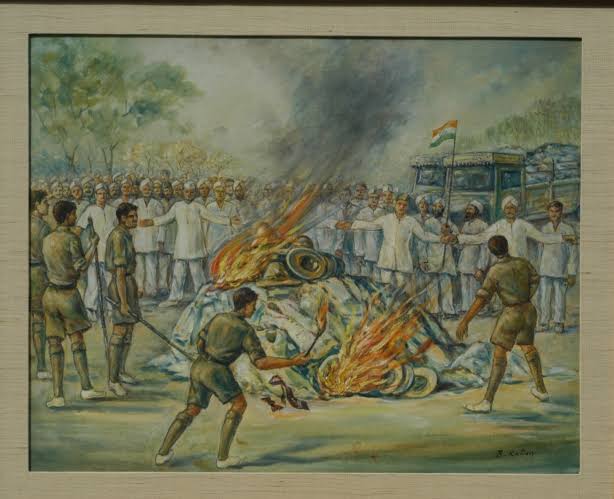

1. Foreign cloth boycott becomes a mass symbol

- Imports dropped dramatically.

- Bonfires of cloth became national rituals.

- Khadi spread across India.

2. Growth of “national schools”

- Gujarat Vidyapith

- Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth

- Jamia Millia Islamia

- National colleges in Punjab and Bengal

Thousands of students enrolled.

3. Volunteer corps

- Congress volunteers trained in discipline and satyagraha.

- Organized picketing of toddy shops and foreign cloth stores.

4. Local rebellions magnified

- Peasant movements in Awadh.

- Eka movement in UP.

- Moplah rebellion in Malabar (complex causes: agrarian + religious + anti-landlord).

Though movements were not always non-violent, they were inspired by Gandhi’s aura and message.

ESCALATION OF TENSIONS

As Non-Cooperation grew, the colonial state felt threatened.

1. Arrest of Nationalist Leaders

- Ali brothers arrested.

- CR Das, Motilal Nehru jailed.

- Gandhi remained free but closely monitored.

2. Repression

- Lathi charges on crowds.

- Press censorship.

- Arrests of satyagrahis everywhere.

Public anger increased.

CHOORI CHAURA INCIDENT (5 FEBRUARY 1922)

This incident changed everything.

1. What Happened

- A peaceful demonstration in Chauri Chaura (Gorakhpur, UP) protested police atrocities.

- Police fired on protesters.

- Enraged crowd set fire to the police station.

- 22 policemen were burned alive.

2. Gandhi’s Reaction

Gandhi was devastated. He believed:

- Non-violence had been compromised.

- People were not ready for a full civil disobedience.

- Moral discipline of the movement was weakening.

Against Congress advice, Gandhi immediately called off the entire Non-Cooperation Movement (11 February 1922).

REACTIONS TO THE WITHDRAWAL

1. Criticism Within Congress

Many leaders were shocked.

- Subhas Chandra Bose called it a “national calamity”.

- Jawaharlal Nehru felt peasants had been left leaderless.

- Motilal Nehru, CR Das believed the movement was at its peak.

2. Supporters of Gandhi

- Believed Gandhi saved the nation from violence.

- Emphasized moral authority over political success.

3. British Response

- Gandhi was arrested in March 1922.

- Sentenced to six years in jail.

- British thought they had ended the mass movement.

SIGNIFICANCE OF NON-COOPERATION MOVEMENT

Even though it ended abruptly, its impact was enormous.

1. Indian nationalism became a mass movement

Millions participated → farmers, workers, students, women.

2. Gandhian methods became nationally accepted

- Non-violence

- Swadeshi

- Khadi

- Moral protest

- Satyagraha

3. Growth of alternative institutions

- National education

- People’s courts

- Village panchayats

- Volunteer groups

4. Hindu–Muslim unity reached a historical peak

Later events would weaken it, but 1920–22 was a rare moment of unity.

5. British legitimacy collapsed

The government understood that:

- Indians could organize on a massive scale

- Violence or detention could not suppress Gandhi’s moral influence

- The Raj was losing the “moral right to rule”

6. Rise of new leaders

- Jawaharlal Nehru

- Subhas Chandra Bose

- Sardar Patel

- Rajendra Prasad

All emerged as national figures during this period

The International Context: World War I and the Ottoman collapse

To understand Gandhi’s mass movements, one must first understand the global political changes taking place around 1918–1920.

End of World War I (1918)

- The Allied Powers (Britain, France, USA) won the war.

- The Ottoman Empire (ruled by the Caliph) was defeated.

- The British planned to punish Turkey by removing the Caliph, who was the religious head for Muslims.

Indian Muslims and the Caliphate

Indian Muslims were deeply concerned because:

- The Caliph was seen as the protector of Islam.

- Harsh penalties on Turkey were seen as an insult to the Islamic world.

- They felt Britain broke its wartime promises to protect the Caliph.

Thus began the Khilafat agitation.

The Khilafat Movement (1919–1924)

What was the Khilafat Issue?

- The Caliph (Sultan of Turkey) was to be removed.

- The Turkish Empire was about to be partitioned.

- Indian Muslims demanded:

- The Caliph must retain his authority.

- Turkey’s territory must not be divided.

- Muslim holy places must remain under Muslim control.

Leaders of the Khilafat Movement

- Maulana Mohammad Ali

- Maulana Shaukat Ali

- Maulana Abul Kalam Azad

- Hakim Ajmal Khan

- Dr. Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari

Demand to Gandhi

Muslim leaders requested Gandhi to lead the protest because:

- They valued his moral leadership.

- They believed Hindu-Muslim unity could strengthen their cause.

- Gandhi had already proven mass mobilization capability in Champaran, Kheda, and Ahmedabad.

Gandhi’s response

Gandhi strongly supported the Khilafat cause because:

- He believed Hindu–Muslim unity was necessary for Swaraj.

- He saw this as the perfect opportunity to unite Indians against British rule.

- Both communities had grievances:

- Muslims: Khilafat issue

- Hindus: Rowlatt Act & Jallianwala Bagh

This unity created unprecedented political energy.

Gandhi’s Strategy: Combine Khilafat + Swaraj

Gandhi convinced Congress to merge:

- Khilafat grievances

- Nationalist grievances

- Demand for Swaraj (self-rule)

This was the first time a national movement brought together:

- Peasants

- Workers

- Students

- Women

- Hindus

- Muslims

- Merchants

- Tribal groups

and made British rule morally illegitimate.

Launch of the Non-Cooperation Movement (1920–1922)

Gandhi’s belief

British rule survived only because Indians cooperated.

If Indians withdrew cooperation, the Raj would collapse peacefully.

The Aim

Swaraj within one year (Gandhi stated this repeatedly).

How?

By non-violent, nationwide refusal of:

- Titles

- Government jobs

- Schools and colleges

- Law courts

- Taxes (in later stage)

- Foreign cloth

- Legislative councils (elections boycott)

- Government events

- Import of British goods

The Formal Resolution (Nagpur Session, December 1920)

Congress accepted:

- Non-Cooperation Movement

- Khilafat demands

- Swaraj as the main national goal

- The use of non-violent methods only

The nationalist movement now turned into a mass mass movement.

Phases of the Non-Cooperation Movement

The movement had three stages:

6.1 First Stage: Surrender of Titles and Boycott of Functions

- Indians returned British titles (Sir, Rai Bahadur, Khan Bahadur).

- During royal visits, Indians boycotted welcome programs.

- Subhas Chandra Bose returned his ICS position.

- Ravindranath Tagore returned his knighthood.

Second Stage: Boycott of Schools, Colleges, Courts

- Students left government institutions.

- National schools like Jamia Millia Islamia and Kashi Vidyapeeth were formed.

- Lawyers like C.R. Das, Motilal Nehru, Lala Lajpat Rai gave up practice.

Third Stage (Planned): Non-payment of Taxes

Not fully implemented except in some regions (like Awadh), because Gandhi wanted:

- Full preparation

- Strict non-violence

- Organizational discipline

Spread of Non-Cooperation Across India

Among Students

- 1 lakh+ students left government schools.

- Youth movements grew.

- New national institutions emerged.

Among Lawyers

Many leading lawyers left their practice:

- C. Rajagopalachari

- Vallabhbhai Patel

- Chittaranjan Das

- Motilal Nehru

This reduced trust in colonial courts.

The Economic Impact: Boycott of Foreign Cloth

Bonfires of foreign cloth

Across India, foreign cloth worth crores was burned.

Rise of Khadi

- Khadi symbolized swadeshi and self-reliance.

- Charkha became a political symbol.

- Thousands of women began spinning.

- Merchants of British cloth suffered heavy losses.

Participation of Peasants

Different regions produced different movements:

Peasants of Awadh

Led by Baba Ramchandra and later Jawaharlal Nehru.

Peasant grievances:

- Excessively high rents

- Illegal taxes (Nazarana, Bedakhli)

- Forced labor

- Beatings by landlords

Demands:

- Reduction of rent

- No forced labor

- Lower revenue

- Social justice

Peasant panchayats strengthened the movement.

The movement often became violent, which worried Gandhi.

The Eka Movement

Another peasant movement in:

- Hardoi

- Sitapur

- Unnao

Reasons:

- Rent enhancement

- Harsh eviction methods

- High usury rates

Though inspired by Non-Cooperation, it turned violent and moved out of Congress control.

Tribal Movements (Andhra, Bengal, Maharashtra)

Tribal groups protested against:

- Forest laws

- Grazing restrictions

- Forced labor

- Police oppression

Notable: The Gudem Rampa Rebellion (Andhra)

Led by Alluri Sitarama Raju.

- Promoted swadeshi

- Inspired by Gandhi, but believed in violent guerrilla tactics

- Focused on freedom from forest laws

Participation of Workers

Textile Workers in Bombay

- Strikes in 1919–1920

- Anti-British sentiments grew

- Demands for better wages

- Support from Congress leaders but often autonomous

Jute Workers in Bengal

- Inspired by nationalist appeals

- Boycott of foreign goods

- Workers aligned with middle-class nationalism

Participation of Women

For the first time:

- Women came out in large numbers

- Picketed liquor shops

- Boycotted foreign cloth shops

- Joined demonstrations

- Participated in spinning khadi

Women from all backgrounds—urban educated, poor peasants, widows—joined the movement.

Why Gandhi Suspended Non-Cooperation (1922)

12.1 The Chauri Chaura Incident (5 February 1922)

At Chauri Chaura (Gorakhpur, UP):

- A peaceful demonstration turned violent

- Protesters were shot at by police

- In retaliation, the crowd burned the police station

- 22 policemen died

Gandhi was shocked because:

- He believed violence destroyed the moral basis of the movement

- The movement was slipping out of control

- India was not ready for total non-violent struggle

Hence, Gandhi suspended the movement nationwide.

This decision deeply disappointed:

- Motilal Nehru

- C.R. Das

- Many young nationalists

But Gandhi kept insisting:

“Freedom cannot be built on the foundation of violence.”

Reactions to the Withdrawal

Disappointment in Congress

Leaders felt:

- A great opportunity had been lost

- British repression had already weakened the Raj

- Masses were energized as never before

Formation of Swaraj Party (1923)

C.R. Das and Motilal Nehru formed the Swaraj Party to:

- Enter legislative councils

- Obstruct colonial policies from within

- Keep the political momentum alive

Gandhi’s View

He believed:

- Councils were “houses of slavery”

- Real work was constructive work:

- Khadi

- Removal of untouchability

- Hindu-Muslim unity

- Prohibition

- Village development

Achievements of Non-Cooperation Movement

First nationwide mass movement

Millions participated:

- Peasants

- Tribals

- Students

- Teachers

- Workers

- Women

Transformation of Indian nationalism

Nationalism became:

- Mass-based

- Emotionally powerful

- Deeply rooted in villages

- Connected to daily hardships

British fear

British realized:

- Gandhi could mobilize the entire country

- The Raj was vulnerable

- Indians had “lost fear of authority”

Strengthened Hindu-Muslim unity

Khilafat and Non-Cooperation created unprecedented unity.

Moral victory

Indians gained:

- Self-confidence

- Collective identity

- Political awakening

Limitations of the Movement

Internal differences

Different groups interpreted non-cooperation differently.

Violence was hard to restrain

Peasants and tribals often used force.

Social divisions

Landlords vs. tenants

Workers vs. mill-owners

Tribes vs. forest officials

Economic hardships

Boycotts meant:

- Shops closed

- Peasants unable to buy salt, kerosene

- Workers lost wages during strikes

Temporary nature

Swaraj within one year did not materialize.

Background to the Civil Disobedience Movement

The withdrawal of the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1922 created a temporary lull in mass nationalism. But anger against the British continued to simmer. Gandhi devoted the next years to constructive programmes:

- Promotion of khadi

- Removal of untouchability

- Advancing Hindu–Muslim unity

- Establishing village industries

- Prohibition of liquor

- Social reform (women’s upliftment, education)

Meanwhile, important developments took place:

The Simon Commission (1927)

- The British government appointed a commission to report on constitutional reforms.

- No Indian member was included.

- This caused countrywide resentment.

- Slogans of “Simon Go Back!” echoed across India.

- Leaders like Lala Lajpat Rai led protests (he later died due to police lathi-charge injuries).

Nehru Report (1928)

In response:

- An all-party committee headed by Motilal Nehru drafted a constitution.

- It demanded:

- Dominion Status

- Bill of Rights

- Federal system

- Responsible government

But Jinnah rejected it, arguing for his “Fourteen Points” to protect Muslim interests.

Lahore Congress (1929) – Declaration of Purna Swaraj

Presided by Jawaharlal Nehru, Congress declared:

- Complete Independence (Purna Swaraj) as the national goal.

- 26 January 1930 to be celebrated as Independence Day.

- Civil Disobedience was approved as next step.

Gandhi was now ready to give a definite direction to Indian struggle.

Why Gandhi Chose Salt as the Issue

Gandhi wrote to Viceroy Irwin (February 1930), listing 11 demands:

- Reduction of land revenue

- Abolition of salt tax

- Cut in military expenditure

- Release of political prisoners

- Lower rupee–sterling ratio

- Protections for Indian textile & coastal shipping

Salt tax was selected for launching the movement, because:

- Salt was used by every Indian, rich or poor.

- Tax on salt symbolized British oppression of the poorest.

- Breaking the salt law was a simple act that could mobilize millions.

This decision was brilliant symbolically:

“Salt is essential for survival; therefore its tax is the most inhuman.”

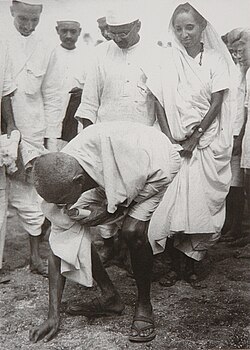

The Dandi March (12 March – 6 April 1930)

Starting Point

- Sabarmati Ashram, Ahmedabad.

Participants

- 78 carefully chosen volunteers:

- Ashram residents

- Untouchables (significant for Gandhi)

- Trusted satyagrahis

The Journey

- 240 miles

- 24 days

- Through villages of Gujarat

- Massive crowds joined daily

This became a spiritual pilgrimage as much as a political march.

Reaching Dandi (6 April 1930)

Gandhi picked up a lump of salty mud and said:

“With this, I am shaking the foundations of the British Empire.”

This symbolic act electrified the nation.

Nationwide Spread of Civil Disobedience Movement

The movement spread like wildfire.

Breaking Salt Laws

People began:

- Making salt near the sea

- Buying and selling illegal salt

- Organizing salt satyagraha in inland areas

Boycott of Foreign Cloth

- Bonfires of foreign cloth resumed.

- Sales of khadi skyrocketed.

Boycott of liquor shops

- Prohibition picketing became widespread.

- Shops saw dramatic declines in sale.

Non-payment of taxes

- In many places, revenue refused.

- Forest satyagrahas emerged.

No-Chowkidar tax movement (Bihar)

- Villagers boycotted paying taxes for village watchmen.

Participation of Women

For the first time:

- Thousands of women participated in picketing and marches.

- Sarojini Naidu became a central figure.

Gandhi’s Arrest (May 1930)

British response:

- Gandhi arrested at night without warning.

- Nationwide protests followed.

- National leaders including Abbas Tyabji, Kasturba Gandhi, Sarojini Naidu were arrested.

Salt satyagraha intensified.

Role of Different Social Groups in Civil Disobedience

The movement had different meanings for different groups.

Peasants

(a) Rich Peasants (Patidars, Jats)

- Benefited during WWI but suffered post-war depression.

- High revenue demands troubled them.

- They strongly supported no-tax movements.

- After Gandhi–Irwin Pact ended tax boycott, they felt betrayed.

(b) Poor Peasants

- Demand: Remission of rent.

- Congress was cautious (didn’t want conflict with landlords).

- Many were disappointed.

Business Classes

Supported the movement because:

- They wanted protection from British imports.

- They hated the colonial exchange rate policy.

Prominent organizations:

- Indian Merchants’ Chamber (IMC)

- FICCI led by Purshottamdas Thakurdas and G.D. Birla

But businessmen feared:

- Escalation to full-scale conflict

- Workers demanding higher wages

- Radical nationalism

Their support waned by 1931.

Industrial Workers

Workers followed:

- Boycott of foreign goods

- Anti-colonial sentiment

But:

- Few strikes took place due to Congress caution

- Communists at times led parallel movements

Women

Women played a major role:

- Picketing

- Making salt

- Leading marches

- Underground activities

- Spinning khadi

This broadened the nationalist social base.

Repression by British Government

Unsparing Brutality

- Lathi charges

- Firing on crowds

- Confiscation of property

- Fines

- Banning of Congress

Salt depots raided

Volunteers beaten mercilessly while walking non-violently toward salt warehouses.

American journalist Webb Miller wrote:

“Not one of the volunteers even raised an arm to fend off blows. It was heartbreaking.”

This brutality exposed the moral bankruptcy of the Raj globally.

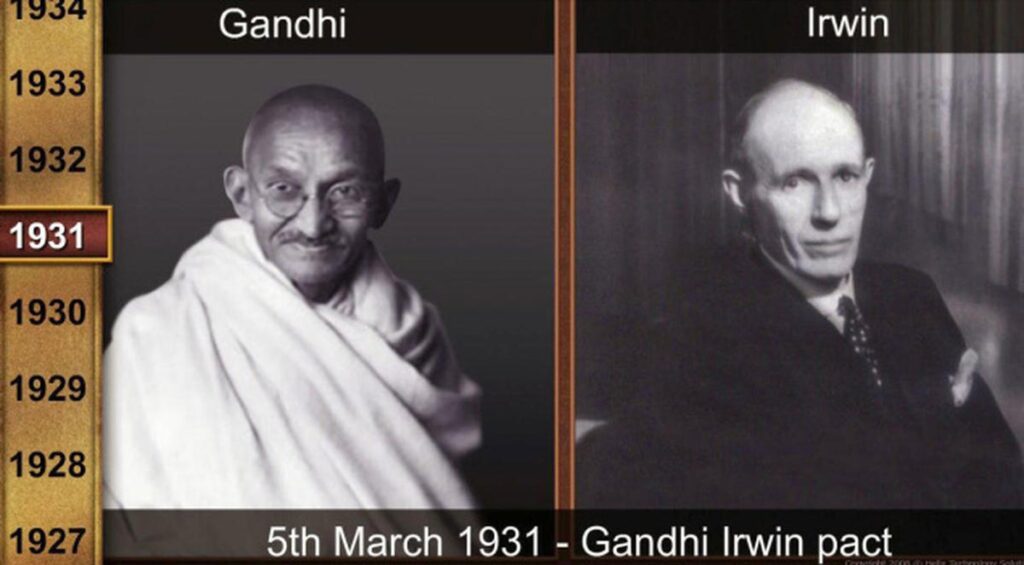

Gandhi–Irwin Pact (March 1931)

After months of repression, the British government sought a compromise.

Terms of the Pact

Gandhi agreed to:

- Suspend the Civil Disobedience Movement

- Participate in the Second Round Table Conference

- Stop all satyagraha activities

British agreed to:

- Release all political prisoners (except violent offenders)

- Allow peaceful picketing

- Withdraw all repressive ordinances

- Return confiscated property (if not sold)

- Permit Indians to make salt on the coast

This was the first time the British recognized the Indian National Congress as representative of Indian people.

Round Table Conferences (1930–1932)

The British held conferences in London to discuss constitutional reforms.

First Round Table Conference (1930)

- Congress boycotted (Gandhi in jail).

- Mostly princes, Anglo-Indians, Muslims, Sikhs participated.

Outcome: No meaningful result.

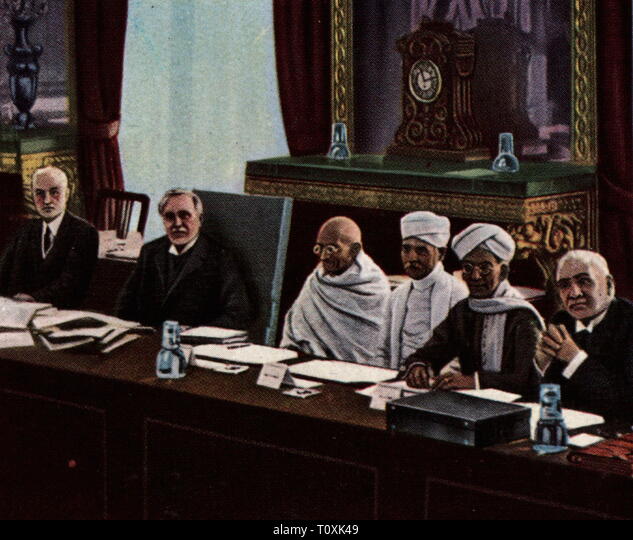

Second Round Table Conference (1931)

Gandhi was the sole representative of Congress.

Major Issues Discussed:

- Minority representation

- Separate electorates for Muslims, Sikhs, Dalits

- Status of Depressed Classes

- Federal structure with princes

- Central–provincial powers

Outcome

- Gandhi disappointed.

- B.R. Ambedkar insisted on separate electorates for Dalits.

- Communal demands overshadowed Swaraj.

- The conference failed.

Gandhi returned disappointed.

Third Round Table Conference (1932)

- Congress again boycotted.

- British proceeded to frame Government of India Act (1935).

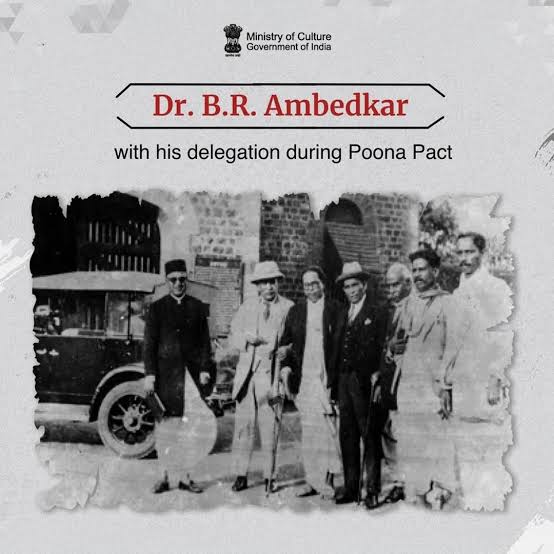

Gandhi’s Fast and the Poona Pact (1932)

Communal Award (August 1932)

British PM Ramsay MacDonald granted separate electorates for:

- Muslims

- Sikhs

- Christians

- Anglo-Indians

- Europeans

- Dalits (“Depressed Classes”)

Gandhi strongly opposed separate electorates for Dalits, calling it:

“A measure that will divide Hindu society forever.”

Gandhi’s Fast unto Death (Yeravada Jail)

Gandhi began a fast against separate Dalit electorates.

This caused:

- Panic among Hindus

- Huge negotiations

- Emotional pressure on leaders of Depressed Classes

Ambedkar–Gandhi Negotiation

Ambedkar argued:

- Separate electorates were essential for political empowerment.

- Dalits were socially oppressed and needed distinct safeguards.

But under massive moral pressure created by Gandhi’s fast, a compromise was reached.

The Poona Pact (24 September 1932)

Terms

- No separate Dalit electorates.

- Dalits to get reserved seats in general electorates.

- Number of reserved seats increased (148 seats instead of 71).

- Adequate representation in government services.

- Provisions for educational facilities.

Significance

- Preserved Hindu social unity (according to Gandhi).

- Provided reservations in politics (according to Ambedkar).

- Became the basis for later scheduled caste reservations.

Ambedkar later wrote that he agreed only due to extreme pressure.

Revival of Civil Disobedience Movement (1932–1934)

After returning from London, Gandhi resumed Civil Disobedience, but:

Conditions were different

- Government passed harsher laws

- Congress declared illegal

- Mass movements weakened

- Economic depression worsened public life

Limited participation

- Peasants frightened

- Businessmen withdrew

- Workers uncertain

End of the Movement

In 1934, Gandhi suspended the movement permanently, believing:

- People were exhausted

- Violent tendencies were rising

- Constructive work was needed

Achievements of Civil Disobedience Movement

Massive participation

Millions participated across all strata.

Legitimization of Gandhi

British recognized Gandhi as the most important Indian leader.

Weakened the Raj

The colonial state was morally and politically shaken.

Federal Constitutional Reform

Movement forced British to pass:

- Government of India Act, 1935

- Provincial autonomy

- Federal structure (not implemented)

- Expanded franchise

Political education of masses

People realized:

- They had political power

- Unity could challenge imperialism

Limitations and Criticisms

Class Conflicts

Different groups had conflicting interests:

- Peasants vs landlords

- Workers vs millowners

- Princes vs Congress

- Upper castes vs Dalits

Limited participation of industrial workers

Congress avoided being labeled “revolutionary socialist”.

Dalit alienation

Ambedkar accused Gandhi of undermining Dalit political independence.

Hindu–Muslim tensions

Khilafat unity was short-lived.

Historical Importance of Civil Disobedience Movement

The largest mass movement before Quit India

Millions participated.

Established satyagraha as dominant Indian strategy

Moral authority became the weapon.

Replaced fear with courage

People lost fear of the government.

Global attention

International media showed British repression.

Gandhi as moral and political symbol

He became:

- Voice of conscience

- Face of the oppressed

- International icon of peace.

Gandhi’s Philosophy, Social Reform Work & National Movements (1935–1942)

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ACT, 1935 AND GANDHI’S RESPONSE

The Government of India Act of 1935 is one of the longest acts ever passed by the British Parliament. It introduced:

- Provincial autonomy

- Federal structure (never implemented)

- Separate electorates for minorities

- More powers to Governors

- Limited political participation for Indians

Gandhi’s Views on the 1935 Act

Gandhi criticized the Act strongly.

He famously said:

“It is a charter of slavery, not freedom.”

Why Gandhi disliked the Act:

- Retained the Governor’s overriding powers

Governors could veto bills, dismiss ministries, and assume command. This meant Indians had no real autonomy. - Communal electorates expanded

Gandhi believed British policy of “divide and rule” was strengthened. - Did not reflect the aspirations of the freedom struggle

After decades of movement, repression, sacrifices, the act still did not grant freedom or sovereignty. - Purposefully complicated

The Act was designed to confuse Indian politics and create divisions. - Unacceptable central control

The centre retained control over defense, finance, and law & order.

CONGRESS MINISTRIES (1937–1939)

Under the 1935 Act, elections were held in 1937.

Congress won major victory in 7 provinces:

- United Provinces

- Bihar

- Madras

- Bombay

- Central Provinces

- Orissa

- Northwest Frontier Province (Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s region)

Gandhi’s Approach to Congress Ministries

Gandhi himself did not take office, nor did he allow top Congress leaders to join governments. His goal:

- Keep Congress primarily a mass movement, not an administrative body.

Achievements of Congress Ministries

Congress ministries undertook progressive reforms:

- Reduction of land revenue in some regions

- Release of political prisoners

- Promotion of village industries

- Expansion of primary education

- Support for Harijan upliftment

- Removal of press restrictions

Why Congress Ministries Resigned in 1939

When the British declared India a participant in World War II without consulting Indians, Congress ministries resigned in protest.

Gandhi remarked:

“When a free nation takes part in war, it does so after a free debate; India was not even consulted.”

THE SECOND WORLD WAR AND THE INDIAN RESPONSE (1939–1942)

Gandhi’s Peace Philosophy

Gandhi, a prophet of non-violence, could not support the British war effort without:

- Promise of Indian freedom

- Democratic consultation

- End of imperialism

Internal Debate within Congress

There was a major debate inside the Congress:

- Gandhi & Nehru: Both were against supporting the British war effort without conditions.

- Subhash Chandra Bose: Wanted an aggressive anti-British stance; formed the Forward Bloc; later INA.

- Patel & Rajagopalachari: More moderate, willing to negotiate.

August Offer (1940)

British offered:

- Expansion of Executive Council

- Minor concessions

Gandhi rejected it, calling it:

“Too little, too late.”

THE INDIVIDUAL SATYAGRAHA (1940–41)

Before starting any mass movement, Gandhi launched Individual Satyagraha.

Why Individual Satyagraha?

- Mass movement could lead to violent outbreaks.

- India was not prepared for a mass upsurge.

- Gandhi wanted to express moral opposition to war.

Demand

The simple but powerful message was:

“Freedom of speech and freedom to oppose war non-violently.”

First Satyagrahi: Vinoba Bhave

Chosen for:

- Moral integrity

- Simplicity

- Gandhian life

Second Satyagrahi: Jawaharlal Nehru

Symbolizing:

- National unity

- Commitment to non-violence

Over 25,000 volunteers courted arrest.

The movement didn’t threaten British rule but signaled:

- Moral dissent

- Public resistance

GANDHI’S CONSTRUCTIVE PROGRAMME

Gandhi believed that political freedom was meaningless without social transformation.

Thus, he developed the Constructive Programme, a list of 18+ reforms.

Key Components

- Khadi & Village Industries

- Promote self-reliance

- End economic dependence on Britain

- Removal of Untouchability (Harijan Work)

Gandhi’s lifelong mission:- Temple entry campaigns

- Wells and schools for Harijans

- Publication of “Harijan” magazine

- Communal Harmony

Gandhi called communal violence a poison.

He traveled extensively during visits to riot-affected areas. - Women’s Upliftment

Gandhi encouraged:- Women’s education

- Participation in movements

- Freedom from purdah and early marriage

- Prohibition

Alcohol, he believed, destroyed families and villages. - Promotion of Basic Education (Nai Talim)

Education should:- Be linked to craft

- Build character

- Create self-supporting individuals

- Health and Hygiene

Gandhi advocated simple living, natural remedies, and cleanliness.

Why Constructive Programme mattered?

- Built grassroots support

- Strengthened self-reliance

- Reduced fear of British

- Prepared the people for future mass struggles

GANDHI VS AMBEDKAR: DIFFERENCES & DEBATES

This is a crucial part of the NCERT chapter and very important for CUET & CBSE.

Background

- Ambedkar was the leader of the Depressed Classes (Dalits).

- Gandhi fought untouchability but favored Hindu unity.

Key Differences

- Poona Pact (1932)

- Ambedkar wanted separate electorates for Dalits for genuine political autonomy.

- Gandhi opposed it, fearing permanent division within Hindu society.

- Gandhi’s fast-unto-death led to a compromise:

Increased reserved seats but no separate electorates.

- Approach to Caste

- Gandhi: Reform caste, remove untouchability, spiritual unity.

- Ambedkar: Abolish caste entirely; sought social revolution.

- Representation of Dalits

- Gandhi believed he could represent all Hindus.

- Ambedkar insisted Dalits needed their own voice, separate from caste Hindus.

Areas of Agreement

- Both sought dignity for the oppressed.

- Both wanted democratic reform.

- Both opposed British divide and rule.

7. GANDHI’S SOCIAL PHILOSOPHY

1. Ahimsa (Non-violence)

Not passive resistance but:

- Courage

- Love

- Self-sacrifice

- Willingness to suffer injustice without retaliation

2. Satyagraha

Truth-force or soul-force:

- Mass participation

- Moral persuasion

- Discipline

- Appeals to the conscience

3. Sarvodaya

Welfare of all:

- Inspired by Leo Tolstoy & Ruskin

- Ethical socialism

- Economic equality

4. Trusteeship

Rich people should hold their wealth as “trustees” for society:

- No violent class struggle

- Ethical redistribution

- Dialogue between labor & capital

5. Simplified Living

Gandhi wore khadi and lived simply to:

- Align with the poorest

- Promote self-reliance

- Oppose Western materialism

8. TOWARDS QUIT INDIA (1937–1942)

By 1942, conditions changed drastically.

Why Gandhi Moved Towards Another Mass Movement?

- Failure of August Offer

British unwilling to concede meaningful reforms. - Japanese Expansion

Japan was advancing in Asia; threat to India grew. - Failure of Cripps Mission (1942)

- Promised Dominion Status after war

- Provinces could opt out (risk of India’s partition!)

Gandhi called it:

- Growing public impatience

People wanted decisive action. - Economic crisis due to war

Inflation, shortages, high taxes. - Moral Stand

Gandhi could not support British war effort while India remained enslaved.

Build-up to Quit India

Gandhi believed:

- India must not be a pawn in the war.

- Independence must be immediate.

- Mass action was inevitable.

His famous slogan emerged:

“Do or Die!”

Which officially launched the Quit India Movement in August 1942 (Part 6).

9. SIGNIFICANCE OF THIS PERIOD IN GANDHIAN POLITICS

Gandhian achievements (1935–42):

- Consolidated mass support

- Deepened social transformation

- Took nationalism to villages

- Empowered women

- Reshaped Congress as mass movement

- Strengthened moral basis of freedom struggle

Failures:

- Could not prevent communal divide

- Could not reconcile with Ambedkar fully

- Economic upliftment limited

- Some viewed constructive programme as unrealistic

Yet Gandhi emerged as:

- Moral leader of India

- Unchallenged mass hero

- Architect of Indian nationalism

QUIT INDIA MOVEMENT, PARTITION, GANDHI’S LAST YEARS, AND HIS LEGACY

THE QUIT INDIA MOVEMENT (1942): THE FINAL MASS STRUGGLE

The Quit India Movement (QIM) became the most decisive, intense, and widespread challenge to British rule.

It pushed India irreversibly toward independence.

Background

By 1942:

- British were losing ground in Asia

- Japanese forces were advancing towards India

- Failures of the Cripps Mission had disillusioned India

- People were suffering from wartime inflation and shortages

Gandhi believed:

“A slave country cannot fight for the freedom of others.”

Gandhi’s Uncompromising Stand

Gandhi demanded British withdrawal from India as a condition for cooperation in the war.

His message to the British was clear:

“Leave India to God. If you cannot, leave her to anarchy — anything is better than foreign rule.”

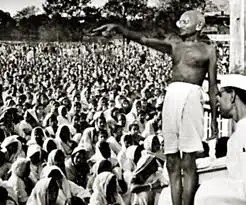

ALL-INDIA CONGRESS COMMITTEE MEETING (8 AUGUST 1942)

Held at Gowalia Tank Maidan, Bombay (now August Kranti Maidan).

Thousands attended, and Gandhi delivered one of his most historic speeches.

The Slogan “Do or Die”

Gandhi said:

“We shall either free India or die in the attempt; we shall not live to see the perpetuation of our slavery.”

This phrase became the soul of the movement.

Aims of the Quit India Movement

- Immediate end to British rule

- Formation of a provisional Indian government

- Mass non-violent resistance

- Freedom as a prerequisite for India’s participation in World War II

The resolution empowered Gandhi to lead a nationwide non-violent revolution.

BRUTAL REPRESSION AND LEADERLESS MOVEMENT

Mass Arrest of Leaders

On early morning of 9 August 1942:

- Gandhi

- Nehru

- Patel

- Azad

- Kripalani

- Rajendra Prasad

- Entire CWC

were arrested without warning.

Gandhi was imprisoned at Aga Khan Palace, Pune, along with Kasturba and Mahadev Desai.

British Repression

- Public meetings banned

- Newspapers censored

- Police firing on protestors

- Lathi charges, arrests, public flogging

- Over 10,000 killed and 60,000 imprisoned

Leaderless Uprising

Despite the arrests:

- Students

- Women

- Workers

- Peasants

- Local Congress workers

took the movement forward spontaneously.

FORMS OF RESISTANCE IN THE QUIT INDIA MOVEMENT

1. Hartals, Prabhat Pheris, Boycotts

People refused to work, attend offices, or cooperate with colonial officials.

2. Attacks on Symbols of British Authority

- Police stations

- Railway lines

- Post offices

- Telegraph wires

were targeted (often without central leadership).

3. Parallel Governments (Prati Sarkars)

In several regions, people established alternative governments:

- Ballia (UP) – Chittu Pandey led a temporary parallel administration.

- Satara (Maharashtra) – “Toofan Sena” (Army of Storms).

- Tamluk (Bengal) – Jatiya Sarkar, complete civil administration.

4. Students as the Backbone

Thousands left schools and joined underground activities:

- Disseminating messages

- Transporting secret communications

- Distributing illegal newspapers

5. Women’s Historic Role

Women emerged as fearless leaders.

Aruna Asaf Ali

- Hoisted the national flag at the Gowalia Tank Maidan on 9 August.

- Became the “Heroine of 1942”.

Usha Mehta

- Ran the underground radio “Secret Congress Radio”.

- Broadcast messages across India.

Women also acted as:

- Couriers

- Shelter providers

- Mobilizers in villages

GANDHI IN PRISON (1942–1944)

Gandhi spent nearly two years in the Aga Khan Palace.

Conditions were harsh.

Personal Tragedies

- Mahadev Desai (secretary) died in 1942.

- Kasturba Gandhi died in 1944 in detention.

He was not allowed to attend her funeral outside the prison.

Gandhi’s Fast (1943)

He undertook a 21-day fast demanding:

- Release of political prisoners

- End to repressive measures

British feared his death would spark rebellion.

Thus, they released him on health grounds (1944).

IMPACT OF THE QUIT INDIA MOVEMENT

1. Final Mass Upsurge

Although suppressed brutally, the British realized:

- They no longer had moral or physical control over India.

2. End of Faith in British Rule

The Indian masses lost all remaining trust in colonial rule.

3. Rise of a New Leadership

A younger generation gained prominence:

- JP Narayan

- Ram Manohar Lohia

- Aruna Asaf Ali

- Nanasaheb Gore

4. International Pressure

Britain was exhausted after WWII.

5. British Cabinet accepted that:

They could not rule India without Indian cooperation.

QIM thus became the turning point towards independence.

GANDHI & THE INA (INDIAN NATIONAL ARMY)

(Though not Gandhi-led, NCERT links this context.)

Subhash Chandra Bose revived the INA.

When INA trials began in 1945:

- Gandhi supported their right to legal defense

- He condemned British actions

- Public sympathy grew massively

INA became a symbol of national pride.

POST-WAR SITUATION & BRITISH NEGOTIATIONS (1945–46)

After WWII ended, waves of unrest rose again:

- Naval Mutiny in Bombay (1946)

- Worker strikes

- INA sympathy

- Mass upsurge in rural areas

British sent:

Cabinet Mission (1946)

Gandhi initially accepted its plan:

- Federal Union

- Interim Government

- No immediate partition

But communal tensions derailed it.

COMMUNAL TENSIONS AND GANDHI’S ROLE

Rise of Muslim League

Under Jinnah, the League demanded:

- Separate nation for Muslims: Pakistan

1946 Direct Action Day

Massive riots in Calcutta.

Thousands killed.

Communal violence spread to:

- Noakhali

- Bihar

- Punjab

Gandhi’s Peace Mission

At age 77, he walked from village to village in Bengal and Bihar, calming riots.

He stayed in:

- Hindu villages

- Muslim localities

- Riot-hit zones

Gandhi walked barefoot for months, saying:

“If India is to be divided, it will be over my dead body.”

But events had gone beyond his control.

TRANSFER OF POWER & PARTITION (1947)

Why Partition Happened

- Breakdown of Congress–League negotiations

- Increasing communal violence

- British desire for quick exit

- Administrative paralysis

- League’s acceptance of nothing short of Pakistan

Mountbatten Plan (3 June 1947)

- India to be partitioned

- Pakistan formed

- Princely states to join either side

- Independence by August 1947

Gandhi’s Reaction

Gandhi was deeply sorrowful.

He refused to celebrate independence and said:

“Today we have won a bad victory.”

GANDHI ON THE EVE OF INDEPENDENCE

While India Celebrated on 15 August 1947…

Gandhi was not in Delhi.

He was in Calcutta, fasting to stop riots.

His presence brought:

- Extraordinary calm

- Religious harmony

- End to violence

This became known as the “Calcutta Miracle.”

GANDHI’S LAST FAST (JANUARY 1948)

Communal violence continued in Delhi.

Refugees demanded revenge.

Armed mobs attacked Muslims.

Gandhi fasted again:

- For Hindu-Muslim harmony

- For protection of Delhi’s Muslims

- For peace between India and Pakistan

A peace agreement was signed by:

- Hindus

- Muslims

- Sikhs

- Government representatives

Gandhi broke his fast only after a written pledge of peace.

ASSASSINATION OF GANDHI (30 JANUARY 1948)

On 30 January 1948, Gandhi was walking for his daily prayer meeting at Birla House, Delhi.

He was shot by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu extremist who accused Gandhi of:

- Favoring Muslims

- Weakening Hindus

- Opposing Partition militancy

His last words were:

“Hey Ram.”

Gandhi’s death shocked the world.

Einstein said:

“Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever walked on this earth.”

GANDHI’S LEGACY

1. Moral Leadership

He transformed:

- Politics → into an ethical movement

- Nationalism → into a mass faith

2. Method of Non-violence

Inspired:

- Martin Luther King Jr.

- Nelson Mandela

- Dalai Lama

- Aung San Suu Kyi

3. Mass Mobilization

Gandhi made:

- Villagers

- Peasants

- Women

- Students

- Harijans

active participants in national politics.

4. Social Revolution

Gandhi challenged:

- Untouchability

- Alcohol consumption

- Caste hierarchy

- Gender inequality

5. Economic Philosophy

- Self-reliance

- Khadi

- Trusteeship

- Gram Swaraj

6. Democracy and Decentralization

Gandhi laid the foundation for:

- Panchayati Raj

- Cooperative movements

7. Critiques of Gandhi

Historians differ:

- Some say he slowed revolution

- Some say he prevented partition

- Some say he facilitated it

- Some say he was too idealistic

Yet all agree:

Gandhi changed Indian history more than any other single leader.

HISTORIOGRAPHY OF GANDHI

Nationalist Historians

- See him as the father of the mass movement

- Attribute freedom to his leadership

Leftist/Marxist Historians

- Criticize his compromises

- Emphasize economic contradictions

Subaltern Historians

- Focus on the voice of the masses

- Gandhi seen as mediator, not controller

International Scholars

- Consider him a global symbol of non-violence

Ambedkarite View

- Gandhi failed to abolish caste

- His reforms did not empower Dalits fully

Modern Evaluation

Despite debates:

- Gandhi’s contribution remains unparalleled

- He reshaped India’s political and moral landscape

FINAL CONCLUSION (FOR EXAMS)

Mahatma Gandhi stands as:

- The moral centre of the Indian freedom struggle

- The architect of non-violent mass movements

- The bridge between India’s villages and its national politics

- A social reformer, philosopher, and spiritual activist

From Champaran to Quit India, his campaigns:

- United millions

- Shattered the myth of British invincibility

- Created new political culture

- Ensured freedom through peace, not violence

His death ended a chapter but started a legacy that continues worldwide.

___________________The End ______________________