Scope: Western Europe, roughly 9th–16th centuries.

Purpose: Explain how medieval society was organised, how it functioned day-to-day, and why it changed.

1. Big picture — what this chapter explains

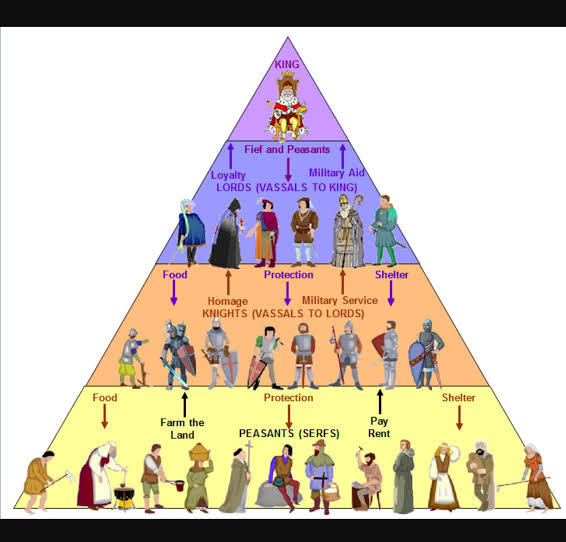

Medieval European society was not a single social class system like modern societies. Instead it was organised around functions — who prayed, who fought, who laboured. Those functional roles became stabilised into a social order: Clergy (pray), Nobility/Knights (fight), and Peasantry (work). This division underpinned politics, economy and culture for centuries and helps us understand the transition from rural, local lordship to towns, commerce and centralised states.

2. The three orders — roles, rights and everyday realities

The idea of the “Three Orders” — what it means

Three Orders = functional social categories used by medieval thinkers (especially clerical writers) to describe society:

Clergy — “Those who pray”

- Who: Popes, bishops, parish priests, monks, nuns.

- Main functions: Conduct religious services, preach, run monastic schools and hospitals, copy books and preserve learning.

- Power & resources: Large landholdings, income from tithe (roughly a tenth of produce), donations and ecclesiastical courts. Clergy had social authority and could influence kings and nobles.

- Everyday reality: Parish priests were local and interacted daily with people; monks ran monasteries that were centres of learning and charity.

Nobility / Knights — “Those who fight”

- Who: Lords, barons, knights — men who owned or administered land and provided military service.

- Main functions: Provide defence, keep order, administer justice locally, collect dues.

- Feudal bond: Lords granted land (a fief) to vassals in return for military service and loyalty. This relationship was formalised by ceremonies (homage, oath of fealty).

- Everyday reality: Knights trained for war, lived in castles, and managed manors; lords held courts and had economic privileges.

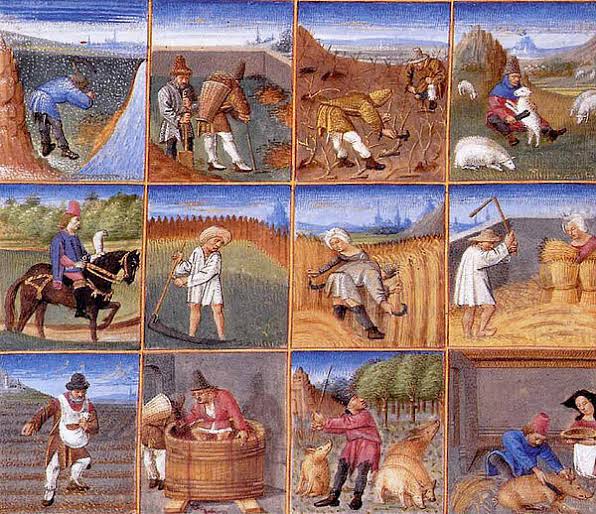

Peasantry — “Those who work”

- Who: Free peasants, villeins (tenant peasants), and serfs (unfree labourers).

- Main functions: Produce food and basic goods; perform corvée labour (work on the lord’s demesne), pay rents and fees.

- Manorial structure: The manor was a largely self-sufficient estate with strips of land farmed by peasants and a central demesne for the lord. Lords provided protection and local justice.

- Everyday reality: Hard physical labour, seasonal work rhythm, obligations (milling, oven, market tolls), limited mobility for serfs.

The concept stressed function (prayer, war, work) rather than modern class identity, and it signalled the moral order and hierarchy that many medieval writers assumed.

3. How the system worked — practical mechanisms

- Fief / Feudal contract: Land was the main currency. A lord gave a vassal a fief; the vassal gave military service and counsel.

- Manorial obligations: Peasants owed labour, produce and money; in return they received plots, protection and access to common resources.

- Local power: Lords exercised judicial powers (manorial courts), which meant law and administration were localised.

4. Economy, technology and daily life

- Agricultural improvements: Heavy iron ploughs, horse collar (shoulder harness), and three-field rotation increased productivity.

- Surplus & markets: Surplus grain supported markets, fairs and the growth of towns — craftsmen and merchants formed guilds to regulate trade and quality.

- Household economy: Most manor households made what they needed; only gradually did money and markets become dominant.

5. Monasteries, churches and cultural life

- Monasteries as hubs: Centres for copying manuscripts, preserving knowledge, providing medical care and hospitality.

- Moral/regulatory influence: Church taught moral codes, sanctioned rulers (“divine legitimacy”), and could discipline rulers through excommunication or interdict.

- Education: Cathedral and monastic schools were precursors to medieval universities.

6. Conflict, crisis and change

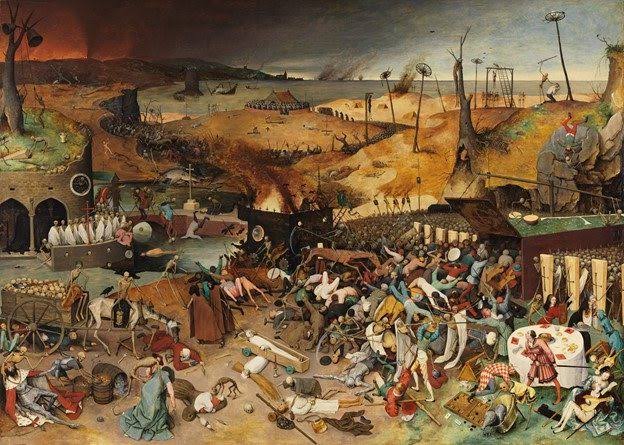

- 14th-century crises: Bad harvests, famines, the Black Death (mid-1300s) and long wars caused massive mortality; labour shortages gave survivors bargaining power.

- Effects: Wages rose in many regions; some lords shifted from labour services to money rents; peasant mobility and urban migration increased.

- Political shift: Kings built standing armies and bureaucracies, reducing the military and judicial autonomy of local lords.

- Economic shift: Growth of towns, commerce and a money economy gradually undercut the old land-for-service system.

7. Regional variation — don’t assume one Europe

- Western Europe (France, England) saw early town growth and commercialisation; Eastern Europe (Poland, Russia) often kept servile relations longer and intensified serfdom in response to grain export demand. Always qualify generalisations.

8. How historians know this (sources & methods)

- Written records: Charters, tax rolls, manorial court rolls, church registers, travelers’ accounts.

- Archaeology: Settlement patterns, pollen studies, tools and castle remains.

- Textual analysis: Chronicles, legal codes, saints’ lives — treated carefully because they mix social ideals with facts.

9. Agricultural and technological changes

- From c. 9th–12th centuries onward, adoption of agricultural improvements (heavy iron plough, horse collar/shoulder-harness, three-field rotation, watermills) increased yields and allowed surplus production. Improved productivity supported population growth and marketable surplus.

10. Growth of towns, trade and the “Fourth” social element

- Surplus production and improved transport encouraged markets, fairs and towns. Urban centres attracted craftsmen and merchants who formed guilds to regulate trade and quality. Over time, these urban groups (burghers / bourgeoisie) became an emergent economic and political force — sometimes called a “fourth order.”

11. The crisis of the 14th century (famines, plague, war) & consequences

- The 14th century saw environmental stress (bad harvests), famine, repeated wars, and the Black Death (mid-14th century). The plague caused catastrophic mortality, producing labour shortages and disrupting traditional labour obligations. Landlords, facing a scarcity of labour, had to offer better terms — wages or rents — which weakened servile obligations and began to erode the manorial system.

- Long-term effects included: social mobility for survivors, higher wages (at least briefly), conversion from labour services to money rents in many regions, growth of towns, and gradual decline of seigneurial power — though processes varied regionally (Eastern Europe retained serfdom longer).

12. Political change: decline of feudal fragmentation and rise of centralised monarchies

- As monarchs built permanent bureaucracies and standing armies and asserted fiscal control, many feudal lords’ local autonomy was reduced. The consolidation of royal authority and shift to monetary economies contributed to the decline of feudal bonds and the transformation toward early modern state structures.

13. How historians interpret “Feudalism” (brief historiography)

- Historians have debated definitions: Ganshof emphasized legal-military lord–vassal ties; Marc Bloch emphasized social and economic relationships including manorialism. Modern scholars stress the varied, regionally different character of feudal institutions rather than a single model.

14. Key terms (quick revision)

- Three Orders — clergy, nobility, peasantry.

- Feudalism — land-for-service relationships (lord–vassal).

- Fief / Fee — land granted to a vassal.

- Manor / Demesne — self-sufficient estate; part farmed for lord.

- Tithe — tenth part of agricultural produce paid to Church.

- Serf / Villein — unfree peasant tied to the land.

15. Conclusion — why this chapter matters

- The “Three Orders” framework helps explain how medieval European society was organised, why certain institutions (monasteries, manors, knights) existed, and why Europe gradually shifted toward towns, market economies and centralized states. Understanding these processes explains the long-term transformations that led to the early modern world.

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive learn anything like this before. So nice to seek out somebody with some authentic ideas on this subject. realy thank you for beginning this up. this web site is something that is wanted on the net, someone with somewhat originality. helpful job for bringing one thing new to the web!