Fully solved question paper with explanation

Section A (Multipal Choice Questions)

Q1. Study the information: Water harvesting for agriculture — reservoir located in Gujarat.

(A) Ropar

(B) Dholavira

(C) Kalibangan

(D) Shortughai

Answer: B — Dholavira.

Explanation: Dholavira (in Kutch, Gujarat) is famous for its sophisticated system of water management — large reservoirs, channels and cisterns used for harvesting and storing rainwater for agriculture and domestic use.

Q2. The most unique aspect of the Harappan cities was the development of

(A) Agriculture

(B) Planned cities

(C) Animal husbandry

(D) Trade

Answer: B — Planned cities.

Explanation: The Harappan settlements are distinguished by grid plans, standardised bricks, organised drainage and public works — features of planned urbanism that set them apart

Q3. Which was the best source of Lapis Lazuli for Harappan sites?

(A) Nageshwar

(B) Shortughai

(C) Manda

(D) Khetri

Answer: B — Shortughai.

Explanation: Shortughai (in northern Afghanistan) was a major source of lapis lazuli in antiquity; Harappan sites obtained lapis through long-distance contacts with such Afghan sources.

Q4. Which is not a factor for Magadha being the most powerful mahajanapada in 600 BCE?

(A) Fine quality of beads found in the forests of Magadha

(B) Accessibility to iron-ore mines

(C) Ganga and its tributaries for communication

(D) Ambitious kings

Answer: A — Fine quality of beads…

Explanation: Magadha’s power derived from strategic location, control of iron resources, riverine communications and strong rulers. The “fine quality of beads in forests” is not a recognised reason for political predominance.

Q5. During which century was the capital of Magadha shifted to Pataliputra?

(A) 5th Century BCE

(B) 4th century BCE

(C) 2nd century BCE

(D) 3rd Century BCE

Answer: B — 4th century BCE.

Explanation: Pataliputra became the prominent capital during the rise of the Nanda and especially the Mauryan dynasty (Chandragupta Maurya — c. 4th century BCE).

Q6. In which language is the ‘Allahabad Pillar Inscription’ composed?

(A) Prakrit

(B) Hindi

(C) Sanskrit

(D) Brahmi

Answer: C — Sanskrit.

Explanation: The Allahabad Pillar inscription (the Prayag Prashasti) praising Samudragupta was composed in classical Sanskrit (written in Brahmi script).

Q7. In which type of marriage does a man keep several wives?

(A) Endogamy

(B) Exogamy

(C) Polygyny

(D) Polyandry

Answer: C — Polygyny.

Explanation: Polygyny = one man, multiple wives. Polyandry = one woman, multiple husbands. Endogamy/exogamy refer to marriage inside/outside a group.

Q8. Identify the social category described: handled corpses, lowest in hierarchy, lived outside village, used discarded utensils, wore clothes of dead and iron ornaments.

(A) Nishadas

(B) Chandalas

(C) Kshatriyas

(D) Malechchas

Answer: B — Chandalas.

Explanation: Chandalas (or chandals) are traditionally described in ancient texts as the outcaste group who performed corpse-handling and were socially ostracised.

Q9. Which pair is correctly matched about places in Buddha’s life?

(A) Birth — Bodhgaya

(B) Place of enlightenment — Sarnath

(C) Preaching — Lumbini

(D) Attainment of Nirvana — Kushinagar

Answer: D — Attainment of Nirvana — Kushinagar.

Explanation: Correct matches otherwise are: Birth — Lumbini; Enlightenment — Bodhgaya; First preaching — Sarnath; Nirvana — Kushinagar.

Q 10. Which of the following is a part of Tripitaka?

(A) Dipavamsa

(B) Dhamma Sutta

(C) Mahavamsa

(D) Abhidhamma Pitaka

Answer: (D) Abhidhamma Pitaka

Explanation:

- The Tripitaka (“Three Baskets”) are the three canonical texts of Buddhism, forming the Buddhist sacred scripture.

- Vinaya Pitaka – rules for monks and nuns.

- Sutta Pitaka (Dhamma Sutta) – teachings and sermons of the Buddha.

- Abhidhamma Pitaka – philosophical and psychological analysis of teachings.

- Among the given options, Abhidhamma Pitaka is directly one of the three baskets of the Tripitaka.

- Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa are later Sri Lankan chronicles, not parts of the Tripitaka.

Q11. Identify the picture and choose the correct answer.

Options:

(A) Amaravati style of art

(B) Statue of Buddha, Mathura in 1st Century AD

(C) Gandhara style of art

(D) Gothic art style

Answer: (C) Gandhara style of art

Explanation:

- The Gandhara school of art flourished in north-western India (modern Pakistan–Afghanistan region) under the Kushanas.

- It combined Greek-Roman (Hellenistic) artistic techniques with Buddhist themes.

- Distinct features: realistic drapery folds, wavy hair, sharp features, and expression of calm spirituality.

- Mathura style developed in red sandstone with Indian influence and less Greco-Roman touch.

- Amaravati belongs to southern India (Andhra) and uses white marble, known for narrative reliefs.

- Gothic is a medieval European Christian style — unrelated.

Note: The following question is only for Visually Impaired Candidates in lieu of question no. 11.

Which art style was used in statues of Buddha found in North India.

(A) Amravati style of art

(B) Mathura art style

(C) Gandhara style of art

(D) Gothic style

Answer : (C) Gandhara style,

Explanation : As Gandhara sculptures of Buddha were mainly found in the north-western region of India.

Q 12. Which of the following travellers was appointed as the Qazi of Delhi by Sultan Muhammad Bin Tughluq?

(A) Abdur Razzaq

(B) Al-Biruni

(C) Ibn Battuta

(D) Barbosa

Answer: (C) Ibn Battuta

Explanation:

- Ibn Battuta (a Moroccan traveller, 14th century CE) visited India during the reign of Muhammad Bin Tughluq (1325–1351 CE).

- The Sultan appointed him as the Qazi (judge) of Delhi due to his Islamic scholarship.

- Later, Ibn Battuta was sent as an ambassador to China from the Delhi court.

- Abdur Razzaq visited India during the Vijayanagara period (15th century).

- Al-Biruni came much earlier, with Mahmud of Ghazni (11th century).

- Barbosa was a Portuguese traveller (16th century).

Q13. Rihla’ is written by which traveller?

(A) Ibn Battuta

(B) Marco Polo

(C) Francois Bernier

(D) Barbosa

Answer: A — Ibn Battuta.

Explanation: Ibn Battuta’s travelogue is called Rihla (an account of his extensive travels across the Islamic world and beyond).

Q14. Identify this traveller:

Doctor, political philosopher and historian; in India 1656–1668 CE; closely associated with Dara Shikoh.

(A) Al-Biruni

(B) Ibn Battuta

(C) Francois Bernier

(D) Abul Fazl

Answer: C — Francois Bernier.

Explanation: François Bernier (French physician and traveller) visited Mughal India (mid-17th century), wrote observations and was connected with Dara Shikoh’s circle.

Q15. Which statements are correct regarding the Lingayats?

(i) They challenged the idea of caste;

(ii) They questioned the theory of rebirth;

(iii) They encouraged practices approved in Dharmashastras;

(iv) They worshipped Shiva in the form of Linga.

Options: (A) (i),(ii) and (iii) (B) (ii) and (iii) (C) (i),(ii) and (iv) (D) All the above

Answer: C — (i), (ii) and (iv).

Explanation: Lingayat (Virashaiva) reform movement (12th century, Basavanna and others) rejected caste hierarchies and Brahmanical ritual authority, questioned orthodox doctrines (including typical Vedic rituals and traditional emphasis on rebirth), and central to their worship was Shiva as the Ishtalinga. They did not promote Dharmashastra-prescribed orthodox practices, so (iii) is incorrect.

Q16. The ‘Nalayira Divyaprabandham’ was frequently described as the —

(A) Tamil Veda

(B) Bengali Veda

(C) Kannada Veda

(D) Dharmashastras

Answer: A — Tamil Veda.

Explanation: The Nalayira Divya Prabandham (the 4000–verse Vaishnava devotional collection) was revered in the Tamil Bhakti tradition and often termed the “Tamil Veda.”

Q17. The walls of Hazara Rama Temple have scenes sculpted from which?

(A) Mahabharata

(B) Ramayana

(C) Jataka stories

(D) Panchatantra

Answer: B — Ramayana.

Explanation: The Hazara Rama Temple (Hampi) contains sculptural panels depicting many episodes from the Ramayana.

Q18. Gajapati rulers ruled over which state?

(A) Orissa

(B) Deccan States

(C) Assam

(D) West Bengal

Answer: A — Orissa (Odisha).

Explanation: The Gajapati dynasty (Kalinga) was the medieval ruling house of Odisha (Orissa), especially strong in the 15th–16th centuries.

Q19. Assertion (A): Vijayanagar empire known for advanced water management.

Reason (R): Rulers constructed embankments and reservoirs along streams from surrounding hills to store rainwater.

(A) Both A & R correct, and R explains A

(B) Both correct, R not correct explanation

(C) A correct, R incorrect

(D) A incorrect, R correct

Answer: A — Both correct and R explains A.

Explanation: Vijayanagara rulers developed tanks, canals, embankments and an extensive system to harvest and store hill runoff — this engineering underpins the assertion.

Q20. Match List-I with List-II (Mughal revenue terms)

- A. Jama — ?

- B. Khet batai — ?

- C. Lang batai — ?

- D. Hasil — ?

List-II: 1. The amount actually collected

2. Dividing after cutting the grain

3. Dividing the field after sowing

4. Amount assessed

Options:

(A) A-4, B-3, C-2, D-1

(B) A-1, B-2, C-3, D-4

(C) A-3, B-3, C-1, D-2

(D) A-4, B-2, C-1, D-3

Answer: (A) A-4, B-3, C-2, D-1.

Explanation:

- Jama = the revenue assessed / state demand (4).

- Khet-batai = division when crop is standing / fields divided after sowing (3).

- Lang-batai = division after crop is cut and stacked — i.e., dividing after cutting the grain (2).

- Hasil = the amount actually collected (1).

Q21. During the Mughal period which tribe engaged in overland trade between India and Afghanistan and also travelled to villages and towns of Punjab?

(A) Sarraff

(B) Koch

(C) Ahom

(D) Lohanis

Answer: D — Lohanis.

Explanation: The Lohanis (Lohani traders/communities) were known historically as merchant/trading groups active in overland trade routes linking north-west India with Afghanistan and were present in Punjab towns and villages.

Section B (Short Answer type questions)

Q 22. (A) Explain any three strategies for procuring materials by the Harappans for craft production. (3)

- Long-distance trade and exchange networks — Harappans imported raw materials (e.g., lapis lazuli from Shortughai/Afghanistan, carnelian from Gujarat/Sindh) through well-established overland and maritime exchange routes connecting the Indus with Iran, Central Asia and the Gulf.

- Local resource exploitation and specialised procurement zones — They exploited nearby raw materials (clay, steatite, copper from Baluchistan/Aravalli foothills, shell from coastal zones) and located craft workshops close to these resource sites to reduce transport costs.

- Controlled procurement via craft specialists and organised production — Archaeological evidence (workshops, standardized weights, seals) indicates organized collection and distribution of raw materials to specialist potters, bead-makers and metallurgists — suggesting planned procurement rather than ad hoc sourcing.

OR

22. (B) Mention any three distinctive features of the burials in the Harappan culture. (3)

- Varied burial types — Harappans used multiple burial forms: urn burials, brick-lined graves, wood coffins and sometimes secondary burials, indicating regional and temporal diversity.

- Grave goods and offerings — Many burials contained pottery, beads, ornaments, copper objects and food vessels — suggesting beliefs in afterlife needs or social display.

- Standardised orientation and placement — Some cemeteries show repeated patterns in body orientation and grave construction, implying ritualised burial practices and community norms regarding the dead.

23. Describe the sources used to construct the history of the Mauryan Empire. (3)

- Literary sources — Indian texts (e.g., Buddhist literature like the Mahavamsa, Jain traditions) and classical foreign accounts (Megasthenes’ Indica via later writers) provide political, social and administrative details.

- Epigraphic evidence — Inscriptions (e.g., Ashoka’s edicts) give direct information on administration, royal policy, dhamma, territorial extent and chronology.

- Archaeological and numismatic evidence — Excavations at Pataliputra and other sites, urban remains, pottery and coins help reconstruct material culture, economy, trade links and state organisation.

24. Briefly describe any three features of the temples built at the time when the Stupa was built at Sanchi. (3)

- Simple structural form and brick/wood use — Early temples were modest, often made of timber or brick, with simple sanctuaries rather than later stone superstructures; they co-existed with stupas as devotional structures.

- Emphasis on yaksha/yakshi and narrative sculpture — Temple doorframes and gateways began to be decorated with sculptural motifs, floral designs and narrative panels similar to stupa reliquary art.

- Association with ritual spaces and community use — Temples functioned as spaces for worship, ritual acts and monastic devotion connected to stupas; their plan emphasised pradakshina (circumambulation) routes and assembly areas.

25. State the inherent problems faced by Al-Biruni in the task of understanding Indian social and Brahmanical practices. (3)

- Language and conceptual differences — Al-Biruni struggled with Sanskrit and had to rely on interpreters and texts; many Indian religious and philosophical concepts had no direct equivalents in Arabic, making translation and understanding difficult.

- Religious and cultural distance — As an outsider and Muslim scholar, he found Brahmanical rituals, caste notions and ritual purity rules culturally alien and had to interpret them cautiously to avoid misrepresentation.

- Reliance on secondary informants and conflicting views — He depended on Brahman scholars and local informants who sometimes presented idealised, sectarian or inconsistent accounts, making objective reconstruction challenging.

26. What was the attitude of Alvars and Nayanars towards the caste system. (3)

- Opposition to caste hierarchy — Both Alvars (Vaishnava bhakti poets) and Nayanars (Shaiva bhakti saints) emphasised devotion (bhakti) over birth-based social status and attacked Brahmanical exclusivity in practice.

- Inclusiveness and social equality — Their poetry and communities accepted devotees from different castes, including lower social groups, thus promoting devotional egalitarianism.

- Critique of ritualism — They criticised formal ritual and caste-based claims to spiritual authority, insisting that sincere devotion and ethical conduct mattered more than social rank.

27. (A) “The geographical location of this place played an important role in the development of Vijayanagara as an empire.” Explain. (3)

- Defensible position and natural fortifications — Vijayanagara (Hampi) lay on a rugged rocky terrain (hills, river islands) that provided natural defence and made it hard for enemies to attack, aiding political stability.

- Control over trade and agrarian resources — Located on the Tungabhadra and near fertile plains and fertile river valleys, it could control irrigated agriculture and inland trade routes linking Deccan, ports and mining areas.

- Strategic crossroads for routes — Its position connected western and eastern Deccan corridors and coastal trade routes, enabling economic prosperity, resource mobilisation and rapid military movement.

OR

27. (B) What do you think was the significance of the rituals associated with Mahanavami Dibba? (3)

- Royal legitimisation and public display — Mahanavami Dibba ceremonies (processions, durbar, public rituals) legitimised the ruler’s sovereignty and displayed royal power before nobles and populace.

- Religious and symbolic functions — Rituals included worship and performance of royal rites linking kingship to divine sanction and auspiciousness for the realm.

- Political mobilisation and social integration — The festival united diverse groups (soldiers, nobles, merchants, peasants) under ceremonial leadership, reinforcing loyalty and a common civic identity.

Section C (Long Answer type questions)

28. (A) Who were the forest dwellers? How did their lives change in the 16th and 17th centuries? (2 + 6 = 8)

Who were the forest-dwellers?

- Definition and composition: Forest-dwellers included tribal communities (Adivasis), shifting cultivators, pastoral groups, hunters-gatherers, and communities dependent on forest produce for subsistence and livelihood.

- Economic activities & social organisation: They practised slash-and-burn or shifting cultivation (swidden), collected minor forest produce (tendu, gum, honey, timber), hunted, grazed livestock and lived in kin-based, often autonomous social groups.

How their lives changed in the 16th–17th centuries

3. Increased demand from expanding states and markets: The rise of large kingdoms and expanding markets (regional/state centres and growing long-distance trade) raised demand for forest produce (timber, tanning bark, saltpetre, dyes), pulling forest economies into market networks.

4. Commercial exploitation and supply for armies/urban centres: Forests were tapped for strategic commodities (timber for shipbuilding/buildings, saltpetre for gunpowder) leading to intensified extraction and labour demands on forest communities.

5. Encroachment, settlement and agrarian expansion: New revenue-seeking elites and zamindars cleared forest tracts for cultivation and settlement; many forest communities lost land or were pushed to marginal areas.

6. Changing labour relations: Some forest groups were absorbed as wage workers, bonded labourers or suppliers in the supply chains of towns and military establishments — reducing their autonomy and turning subsistence producers into market suppliers.

7. Incorporation into state structures and patronage: Certain groups came under state control or received grants; some chiefs negotiated with rulers for protection or offices, thereby altering internal social structures and authority relations.

8. Cultural and social transformations: Increased contact with non-tribal populations led to partial sedentarisation, adoption of new crops, changes in dress/rituals, and in some regions conversion to Islam/Hindu sectarian affiliations—producing hybrid identities.

9. Resistance and adaptation: While many communities adapted through migration, alliance or labour diversification, others resisted encroachment (localised conflicts, flight to interior forests), showing a variety of responses rather than uniform decline.

28. (B) Describe the caste system and rural environment of Mughal India. How were caste panchayats important in village society during the Mughal period? (4 + 4 = 8)

Answer: Caste system and rural environment of Mughal India

- Complex social stratification: Village society was organised into numerous jatis (occupational groups) and broader varna categories; caste identity regulated occupation, marriage, ritual status and social interaction.

- Occupation and economic interdependence: Rural economy depended on specialization — peasants, artisans, weavers, potters, blacksmiths, oil-pressers — creating interdependent caste-based production networks within the village.

- Land relations and hierarchy: Landholding patterns (ryots, small cultivators, village chiefs or lambardars, and zamindars) shaped economic power. Higher status castes often had greater access to land and local authority, while lower castes provided service occupations.

- Physical and institutional organisation: Villages had commons (grazing, waste), shared irrigation and community resources; social control combined custom, caste norms and links with state revenue officials and local elites.

Importance of caste panchayats in village society

5. Local dispute resolution: Caste panchayats (councils) settled family, marriage, property and intra-caste disputes quickly and according to customary norms, reducing reliance on distant state courts.

6. Maintenance of social norms: Panchayats enforced norms of purity, marriage rules, occupational duties and sanctions (fines, exclusion) — thereby reproducing caste identity and social order.

7. Economic regulation: They regulated prices, quality of goods and services for members (e.g., artisan guild norms), and organised collective labour or mutual help during agricultural operations and festivals.

8. Political interface and legitimacy: Caste panchayats acted as intermediaries between villagers and state officials or zamindars (mobilising labour, collecting levies), and offered legitimacy to local leaders — sometimes cooperating with or resisting state demands.

29. (A) Identify the relationship between Sufi saints and the state from the 8th to 18th centuries. (8 points)

- Early autonomy and spiritual authority: From the early medieval period Sufi saints established khanqahs and khanqah-centres independent of the state, gaining moral authority through asceticism, miracles and devotional appeal.

- Sources of political legitimacy: Rulers frequently sought the spiritual blessing (baraka) of prominent Sufis to legitimize rule; royal patronage of saints conferred divine sanction on kingship.

- Patronage and land grants: States and elites endowed Sufi khanqahs with land (waqf), revenue grants and gifts; many Sufi institutions thereby accumulated economic resources and local influence.

- Mediation and social intermediation: Saints mediated between rulers and subjects — they interceded on behalf of petitioners, calmed rebellions, and helped integrate newly conquered populations.

- Local and regional influence: Sufi orders (Chishti, Suhrawardi, Naqshbandi, Qadiri) became embedded in local society, creating broad networks that rulers sought to co-opt for administrative reach.

- Occasional tensions and resistance: Some saints opposed specific rulers or policies (e.g., moral critiques by saints like Nizamuddin Auliya of overreaching sultans), resulting in strained relations or limited confrontation.

- Role under Mughal rule: Mughal emperors (e.g., Akbar) patronised Sufis as a means to broaden support and legitimize syncretic policies; later emperors also used Sufi networks for social control and integration of diverse populations.

- Political instrumentalisation and autonomy: While many Sufis accepted royal patronage, others maintained independence; the relationship was dynamic—mutual accommodation, occasional conflict, and sometimes politicisation of Sufi networks by ambitious rulers.

29. (B) Explain the main beliefs and teachings of the Chishtis during the medieval period.

- Emphasis on love and devotion to God: The Chishti order stressed intense personal devotion (ishq) and love for God as central to spiritual life.

- Service (khidmat) to humanity: Chishti saints emphasised serving the poor and needy as a central religious duty — feeding the hungry and caring for the sick at khanqahs.

- Poverty and renunciation: Chishtis practised voluntary poverty and simple living; the saint’s detachment from worldly wealth was a moral ideal.

- Sama (listening/music) and devotional practices: The order accepted devotional music (qawwali, sama) and poetry as legitimate means to evoke spiritual experience and communal devotion.

- Tolerance and inclusiveness: Chishti teachings were marked by tolerance, openness to people of different castes and faiths, and an emphasis on spiritual equality.

- Use of poetry and Persianate literary culture: Chishti saints used Persian and local vernacular poetry to communicate mystical ideas and reach wider audiences.

- Khanqahs as social centres: Their hospices (khanqahs) became centres of spiritual teaching, social welfare, hospitality and cross-community encounter.

- Ethic of compassion and inner purification: The Chishti path emphasised inner purification, remembrance (dhikr), ethical conduct and compassion as markers of true spiritual progress.

30. (A) Discuss the evidence which shows that Brahmanical rules of brotherhood and marriage were not universally followed.

- Dharmashastra recognition of multiple forms: The Dharmashastras themselves list multiple forms of marriage (e.g., eight types in Manu), implying diversity and that Brahmanical ideal was not the only practice.

- Presence of alternative marital customs: Historical sources and ethnographic records show practices such as sororate and levirate, widow remarriage in some communities, polyandry in certain regions, and cross-cousin marriages — differing from Brahmanical prescriptions.

- Buddhist and Jain literature: These sources narrate social practices (monastic codes, household patterns) and sometimes criticise Brahmanical norms, indicating coexisting, alternative social orders.

- Status of marriage varied by class and region: Rulers, mercantile groups and tribes often followed different marriage norms shaped by economic and political needs; e.g., political alliances via marriage among ruling clans followed patterns not identical to Brahmanical ideals.

- Archaeological and inscriptional evidence: Inscriptions recording endowments, local disputes and legal cases often reflect customary practices and settlements outside Brahmanical frameworks, demonstrating local legal pluralism.

- Occupational and tribal groups’ customs: Artisan and tribal groups maintained customary marriage and brotherhood rules tied to occupation and kinship which diverged from Brahmanical prescriptions.

- Women’s status and remarriage practices: Evidence from certain regions shows widows remarrying and women exercising rights in property or household matters, contrary to strict Brahmanical ideals of widow chastity and exclusion.

- Regional and historical flexibility: Over time and across regions, social practices adapted to economic pressures, migration and local customs — showing that Brahmanical rules were influential but not universally enforced or practiced.

30. (B) Explain why in Sixth century B.C.E. the patriarchal system may have been important in specific families. (8 points)

- Control over property and inheritance: In agrarian households, patrilineal inheritance ensured clear transfer of land and resources through the male line—important for economic stability.

- Lineage consolidation and descent: Patriliny helped maintain and legitimise lineages, clan identity and descent rights which were crucial for claims over kin property and political standing.

- Military and political considerations: In a period marked by formation of polities and warfare, male-centred households and male leadership facilitated mobilisation of fighting men and alliances.

- Agrarian production needs: The division of agricultural labour often privileged male control over ploughing, irrigation and village-level collective tasks, making male authority practically useful.

- Social order and authority: Patriarchy provided a public-facing authority figure (the household head) who could represent the family in village councils, tribute relations and legal matters.

- Control of marriage alliances: Male elders arranged marriages to create alliances, control dowries/wealth transfers, and thereby consolidate political and economic networks.

- Religious and ritual functions: Men often performed ancestral rituals and public religious duties that linked family honour to male ritual performance and continuity.

- Protection of property through regulation of sexuality: Patriarchy regulated women’s sexual conduct and marriage to secure legitimate male lineage and inheritance, seen as important where property transmission mattered.

Section D ( Source Based Questions

Read the source, given below carefully and answer the question that follow:

(1+2+1=4)

What the king’s officials did

Here is an excerpt from the account of Megasthenes: Of the great officers of state, some… superintend the rivers, measure the land, as is done in Egypt, and inspect the sluices by which water is let out from the main canals into their branches, so that every one may have an equal supply of it. The same persons have charge also of the huntsmen, and are entrusted with the power of rewarding or punishing them according to their deserts. They collect the taxes, and superintend the occupations connected with land; as those of the woodcutters, the carpenters, the blacksmiths, and the miners.

Q 31.1 For what purpose were the king’s officials appointed? (1)

They were appointed to administer and supervise agricultural resources and related occupations — especially to manage irrigation and water supply, regulate land measurements and collect taxes so that the state and people received an equitable supply and dues.

Q 31.2 Explain the type of jobs carried out by these officials. (2)

- Water and land management: They superintended rivers, measured land (like in Egypt) and inspected sluices to regulate distribution of canal water so every farmer got an equal supply.

- Administrative and occupational supervision: They oversaw huntsmen (with power to reward or punish), collected taxes, and supervised skilled workers such as woodcutters, carpenters, blacksmiths and miners.

Q 31.3 What was the need to superintend the work of the workmen? (1)

To ensure efficient production, maintain standards and supplies (for public works, military and economy), prevent mismanagement or fraud, and secure orderly delivery of goods/services required by the state and society.

32. Read the source, given below carefully and answer the question that follow: (1+2+1-4)

The system of varnas

This is Al-Biruni’s account of the system of varnas:

The highest caste are the Brahmana, of whom the books of the Hindus tell us that they were created from the head of Brahman. And as the Brahman is only another name for the force called nature, and the head is the highest part of the… body, the Brahmana are the choice part of the whole genus. Therefore the Hindus consider them as the very best of mankind.

The next caste are the Kshatriya, who were created, as they say, from the shoulders and hands of Brahman. Their degree is not much below that of the Brahmana.

After them follow the Vaishya, who were created from the thigh of Brahman.

The Shudra, who were created from his feet…

Between the latter two classes there is no very great distance. Much, however, as these classes differ from each other, they live together in the same towns and villages, mixed together in the same houses and lodgings.

32.1 Why were Brahmanas considered superior? (1)

According to the Hindu creation myth Al-Biruni cites, Brahmanas were said to be created from the head of Brahman; since the head is the highest part of the body, Brahmanas were regarded as the choicest and thus superior.

32.2 How did Al-Biruni disapprove the notion of caste pollution? (2)

- He points out that “between the latter two classes there is no very great distance,” indicating small social distance between some varnas (Vaishya and Shudra), questioning rigid hierarchy.

- He observes that all classes “live together in the same towns and villages, mixed together in the same houses and lodgings,” which contradicts strict ideas of pollution and absolute social segregation.

32.3 Who lived together yet segregated? (1)

Members of the four varnas (Brahmana, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra) lived together in the same towns and villages and even shared houses, despite their hierarchical differences — i.e., different varna groups co-resided though status distinctions remained.

33.Read the source, given below carefully and answer the question that follow: (1+2+1-4)

Colin Mackenzie

Born in 1754, Colin Mackenzie became famous as an engineer, surveyor and cartographer. In 1815 he was appointed the first Surveyor General of India, a post he held till his death in 1821. He embarked on collecting local histories and surveying historic sites in order to better understand India’s past and make governance of the colony casier. He says that “it struggled long under the miseries of bad management… before the South came under the benign influence of the British government”. By studying Vijayanagara, Mackenzie believed that the East India Company could gain “much useful information on many of these institutions, laws and customs whose influence still prevails among the various Tribes of Natives forming the general mass of the population to this day”.

33.1 Who was Colin Mackenzie? (1)

Colin Mackenzie (born 1754) was an engineer, surveyor and cartographer who became the first Surveyor-General of India in 1815 and held that post until his death in 1821.

33.2 How did Mackenzie try to rediscover the Vijayanagara Empire? (2)

- He surveyed historic sites (archaeological remains, monuments and ruins) connected with Vijayanagara.

- He collected local histories and traditions — documenting institutions, laws, customs and inscriptions — combining field survey with documentary gathering to reconstruct the past.

33.3 How was the study of the Vijayanagara Empire useful for the East India Company? (1)

By studying Vijayanagara’s institutions, laws and customs, the Company hoped to gain practical knowledge about local social and political structures that still influenced native populations — information that would make colonial governance and administration easier and more effective.

Section E (Map based question)

(Map Based Question)

(1×5-5)

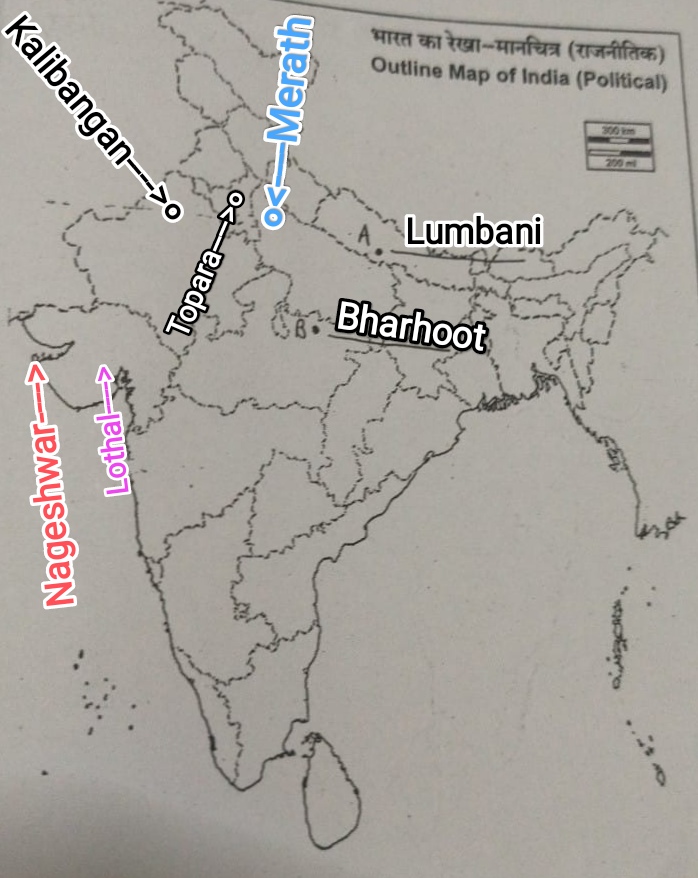

- 34.1 On the given political map of India locate and label the following places with appropriate symbols:

(1+1+1=3)

A. Kalibangan – A Harappan site

B. Nageshwar – A Harappan site

Meerut – A pillar inscription of Asoka

OR

Topra – A pillar inscriptional Asoka

34.2 On the same outline map two major Buddhist sites are marked as A and B. Identify them and write their correct names on the lines drawn near them.

NOTE: The following questions are for visually impaired candidates only in place of question number 34.

Q 34.1 Who was Sir John Marshall?

Answer: Sir John Marshall was the Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) from 1902 to 1928.

Q 34.2 What was Lapis Lazuli?

Answer: Lapis Lazuli was a semi-precious blue stone used in jewellery and ornamentation.

Q 34.3 Name the Harappan site where work was done with shells?

Answer: The Harappan site famous for shell working is Nageshwar (near the coast of Gujarat).

Q 34.4 In which Pitaka are the teachings of Buddha?

Answer: The Sutta Pitaka contains the teachings and sermons of the Buddha.

Q34.5 According to the Rigveda, who is the god of fire?

Answer : According to the Rigveda, the god of fire is Agni.

What excellent interlocutors 🙂

——

https://anyflip.com/homepage/wkmdh

What charming idea

——

https://ssl.by/tags/it-%D0%B8%D0%BD%D1%84%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%82%D1%80%D1%83%D0%BA%D1%82%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B0/

Absolutely with you it agree. It seems to me it is very excellent idea. Completely with you I will agree.

——

https://members5.boardhost.com/lonestarsoftball/msg/1762716450.html